The electronics for motion control systems, routers, and 3D printers are split into two camps. The first is 8-bit microcontrollers, usually AVRs, and are regarded as being slower and incapable of cool acceleration features. The second camp consists of 32-bit microcontrollers, and these are able to drive a lot of steppers very quickly and very smoothly. While 32-bit micros are obviously the future, there are a few very clever people squeezing the last drops out of 8-bit platforms. That’s what the Buildbotics team did with their ATxmega chip — they’re using a clever application of DMA as counters to drive steppers.

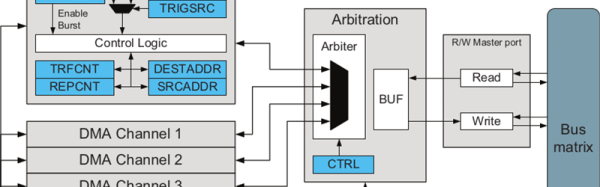

The usual way of driving steppers quickly with an ATMega or other 8-bit microcontroller is abusing the hardware timers. It’s quick, but there is a downside. It takes time for these timers to start and stop, and if you’re doing it two hundred times per second with four stepper motors, that clock jitter will ruin your CNC machine. The solution is to use a DMA channel to count down, with each count sending out a pulse to a stepper. It’s a clever abuse of the hardware, and the only drawback is the micro can’t send more than 2¹⁶ pulses per any 5ms period. That’s not really an issue because that would mean some very, very fast acceleration.

The Buildbotics team currently has a Kickstarter running for their four-axis CNC controller using this technique. It’s designed for Taig mills, 6040 routers, K40 lasers, and other various homebrew robots. It’s an interesting solution to the apparent end of the of the age of 8-bit microcontrollers in CNC machines and certainly worth checking out.