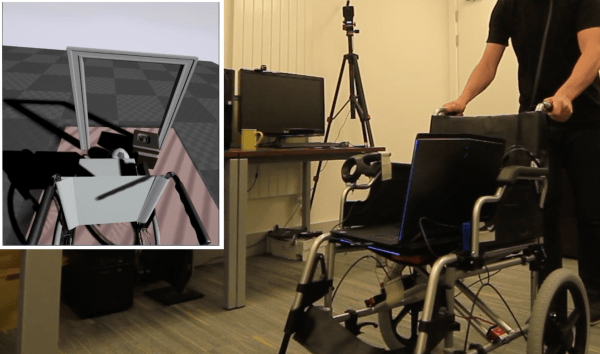

[Jeremy Cook]’s latest take on the Strandbeest, the ClearWalker, is ready to roll! He’s been at work on this project for a while, and walks us through the electronics and control system as well as final assembly tweaks. The ClearWalker is fully controllable and includes a pan and tilt camera as well as programmable LED segments, and even a tail.

[Jeremy Cook]’s latest take on the Strandbeest, the ClearWalker, is ready to roll! He’s been at work on this project for a while, and walks us through the electronics and control system as well as final assembly tweaks. The ClearWalker is fully controllable and includes a pan and tilt camera as well as programmable LED segments, and even a tail.

When we last saw [Jeremy] at work on this design, it wasn’t yet functional. He showed us all the important design and assembly details that went into creating a motorized polycarbonate version of [Theo Jansen’s] classic Strandbeest design; there’s far more to the process than simply scaling parts up or down. Happily, [Jeremy] is able to show off the crystal clear beauty in his photo gallery as well as a new video, embedded below.

Continue reading “Watch The ClearWalker Light Up And Dip Its Toes”