[S.PiC] has been working on a computer case styled to look like the Vulture mech from Battletech. We’re not sure if his serious faced cat approves or not, but we do.

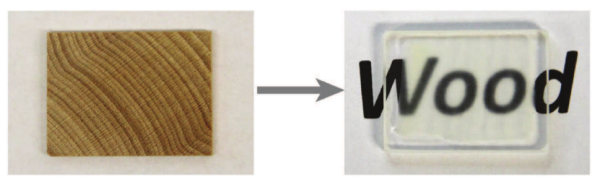

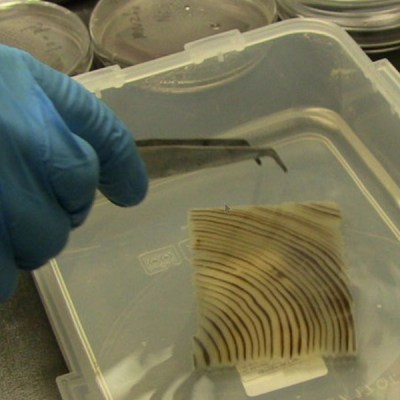

The case is made from artfully cut plywood. We kind of hope he keeps the wood aesthetic. However, that would be getting dangerously close to steampunk. So perhaps a matching paint job at the end will do. In some of the videos we can how he’s cleverly incorporated the computer’s components into the design of the case. For example, the black mesh on the front actually hides the computer’s power supply intake fan.

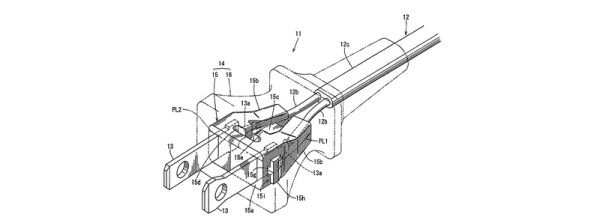

The computer inside is a small micro-itx formfactor one. Added as peripherals to it [S.Pic] has pulled out the hacker-electronics-tricks bible. From hand soldered LED grids to repurposed Nokia LCD screens, he has it all. In one video we can even see the turret of the mech rotating under its own power.

It looks like the build still has a few more steps before completion, but it’s already impressive enough to be gladly worth the useful table space consumed on any hacker’s desk. Video after the break.

Continue reading “Battletech Case Mod Displays Awesome Woodwork, Hides Hacks”