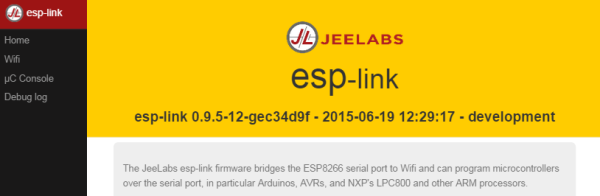

These days, connecting your microcontroller project to a WiFi network is pretty easy — you connect up an ESP8266 to your microcontroller project and pretend it’s a WiFi modem, using these old-school-style AT commands. But what do you do if you need to flash new code into the microcontroller? You can’t reprogram the micro remotely through the ESP8266 because those stupid AT commands get in the way.

The solution? By flashing the esp-link firmware into your ESP8266, you talk directly to the microcontroller over WiFi as if it were connected by a serial cable: the ESP8266 becomes a totally transparent WiFi-serial bridge. Now, with a serial bootloader and an ESP8266 in Wifi-to-serial bridge mode, you can reflash your microcontroller wirelessly, and then telnet in to interact with and debug the system remotely. Once you’ve fixed the bugs, you can re-flash the microcontroller: all over WiFi, without having to climb up a ladder to reach your IoT attic-temperature sensor.

To flash a connected Arduino, for instance, all you need to do is convince AVRDUDE to use the network instead of a locally-connected USB-serial cable: avrdude -p m328p -c arduino -b 115200 -P net:192.168.1.123:23 -U:yourHexFile.hex. The ESP8266 passes the data straight through its TX and RX lines to your microcontroller and everything works as if it were wired.

Configuration to allow the ESP8266 to join your WiFi network takes place on a self-hosted webpage that uses [Sprite_tm]’s esp-httpd standalone server, which makes setup pretty painless. And then after that you can simply telnet to the ESP8266 at port 23 and type away, or do anything else you would with a wired serial connection.

Although the simple bridge mode came first, esp-link looks like it’s growing to be a one-stop shop for all your IoT or microcontroller + WiFi needs. In addition to the serial bridge code, there is also a REST-based microcontroller-to-internet mode and there is bi-directional MQTT support in the wings. We haven’t had a chance to dig into these yet, so if you have, let us know in the comments.

If you want to dig in deeper, head over to [Jeelabs]’ blog for a slightly outdated tour of the project written by the code’s author, [Thorsten von Eicken]. For the most up-to-date development news, follow the very active development of esp-link in this thread on the esp8266 forums.