USB power banks – huge batteries that will recharge your phone or tablet – are ubiquitous these days. You can buy them at a gas station or from your favorite online retailer in any capacity you would ever want. Most of these power banks have a tremendous shortcoming; they need to charge over USB. With a 10,000 mAh battery, that’s going to take a while.

We already have batteries with huge capacities, are able to charge quickly, and judging from a few eBay auctions, can be picked up for a song. [Kumar] is working on a device that leverages these batteries – and the electronics inside of them – to build a smarter power bank.

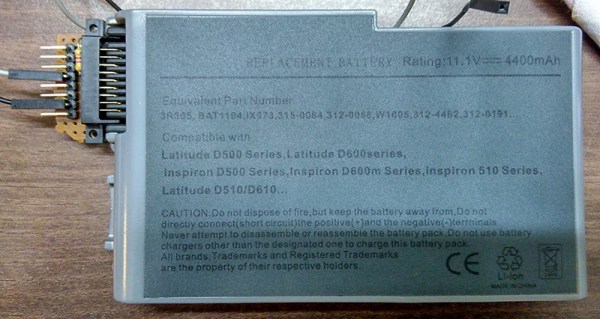

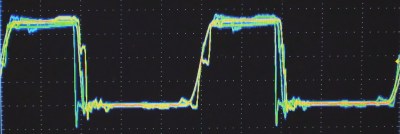

Right now, [Kumar] is working with Dell Latitude D5xx/D6xx replacement batteries that he can pick up easily. These batteries have an SMBus interface, and with a low power ARM microcontroller and a TI BQ24725a, he has everything he needs to efficiently and safely charge these batteries.

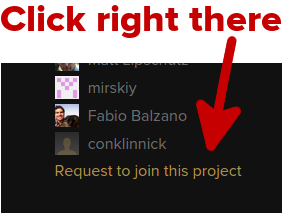

[Kumar] says he’s looking for some community suggestions and feature requests for his project. If you have any, be sure to drop them over on his project page.

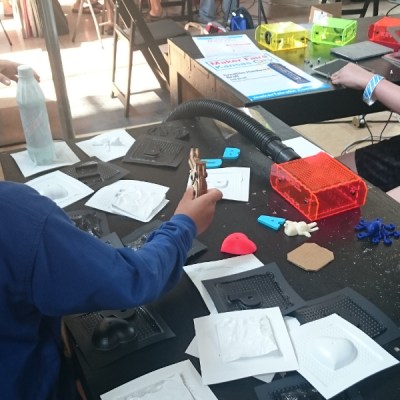

Kevo is a simple and affordable solution for makers of all stripes. It can be used to make molds, blister packaging for items, or even electronics enclosures. [Ted]’s

Kevo is a simple and affordable solution for makers of all stripes. It can be used to make molds, blister packaging for items, or even electronics enclosures. [Ted]’s