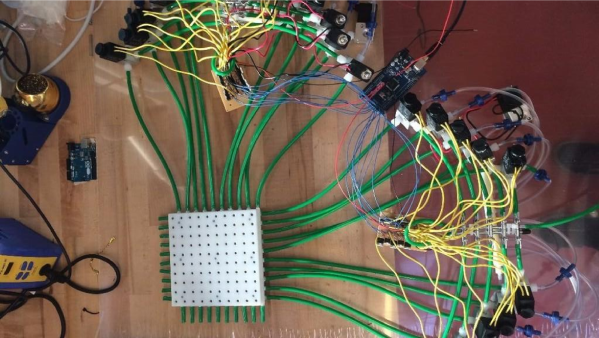

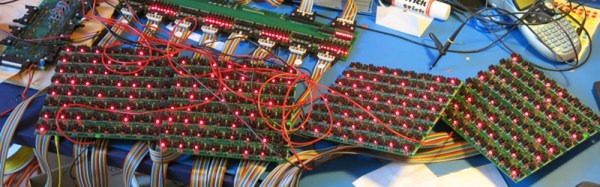

[SuperUnknown] has revealed a secret project he’s been working on. He’s cooked up an EDM attachment for 3D printers, or any CNC machine for that matter. Electrical Discharge Machining (EDM) is a method of using sparks to machine metal. EDM isn’t a new technology, in fact commercial machines have been around since the 1960’s. If you’ve ever had an arc scar up your multimeter probes, you’ve unwittingly done a bit of EDM.

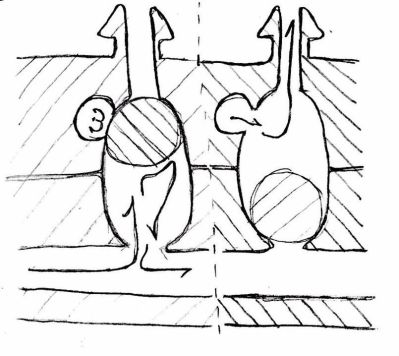

The theory behind EDM is simple: High voltage between the tool and workpiece causes sparks to jump between them. Each spark erodes the workpiece (and the tool). Big EDM machines perform their magic in a liquid which acts as both a dielectric and a flushing medium. This liquid can be anything from deionzed tap water to specially formulated oil. [SuperUnknown] is using good old-fashioned tap water.

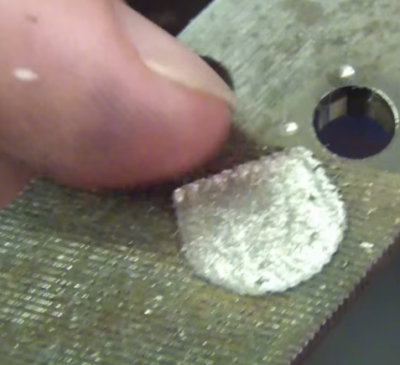

As you can imagine, a single spark won’t erode much metal. EDM machines fire tens of thousands of times per second. The exact frequencies, voltages, and currents are secrets the machine manufacturers keep close to their chests. [SuperUnknown] is zeroing in on 65 volts at 2 amps, running at 35 kHz. He’s made some great progress, gouging into hardened files, removing broken taps from brass, and even eroding the impression of a coin in steel.

As you can imagine, a single spark won’t erode much metal. EDM machines fire tens of thousands of times per second. The exact frequencies, voltages, and currents are secrets the machine manufacturers keep close to their chests. [SuperUnknown] is zeroing in on 65 volts at 2 amps, running at 35 kHz. He’s made some great progress, gouging into hardened files, removing broken taps from brass, and even eroding the impression of a coin in steel.

While we’d love to say this is a free open source project, [superUnknown] needs to pay the bills. He’s going with crowdsourced funding. No, not another Kickstarter. This project is taking a different route. The videos of the machine will be uploaded to YouTube and visible to [superUnknown’s] Patreon supporters. They will also be available for rent using YouTube’s new rental system. [SuperUnknown] has pledged to figure out a way to make the content available for starving college students and others with limited incomes.

Based upon his previous adventures with lil’ screwy, his homemade 100 ton press, and various other projects on the Arduino verses Evil YouTube channel, we think [superUnkown] has a pretty good chance of making home EDM work. Click past the break to see two videos of the 3D printer EDM toolhead in action. We should mention that [SuperUnknown] is rather colorful with his dialogue, so make sure you’re using headphones if you’re at work.

Continue reading “Machine Metal With Electricity: An EDM Attachment For 3D Printers”

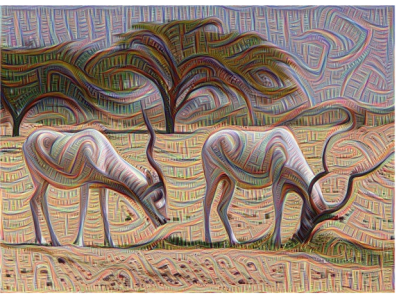

mind, however, is a simple question Google asked, and the resulting answer. To better understand the process, they wanted to know what was going on in the inner layers. They feed the network a picture of a truck, and out comes the word “truck”. But they didn’t know exactly how the network came to its conclusion. To answer this question, they showed the network an image, and then extracted what the network was seeing at different layers in the hierarchy. Sort of like putting a serial.print in your code to see what it’s doing.

mind, however, is a simple question Google asked, and the resulting answer. To better understand the process, they wanted to know what was going on in the inner layers. They feed the network a picture of a truck, and out comes the word “truck”. But they didn’t know exactly how the network came to its conclusion. To answer this question, they showed the network an image, and then extracted what the network was seeing at different layers in the hierarchy. Sort of like putting a serial.print in your code to see what it’s doing. This technique gives them the level of abstraction for different layers in the hierarchy and reveals its primitive understanding of the image. They call this process

This technique gives them the level of abstraction for different layers in the hierarchy and reveals its primitive understanding of the image. They call this process