Yesterday we published a first look at the hardware found on the DEF CON 27 badge. Sporting a magnetically coupled wireless communications scheme rather than an RF-based one, and an interesting way to attach the lanyard both caught my attention right away. But the gemstone faceplate and LED diffuser has its own incredible backstory you don’t want to miss.

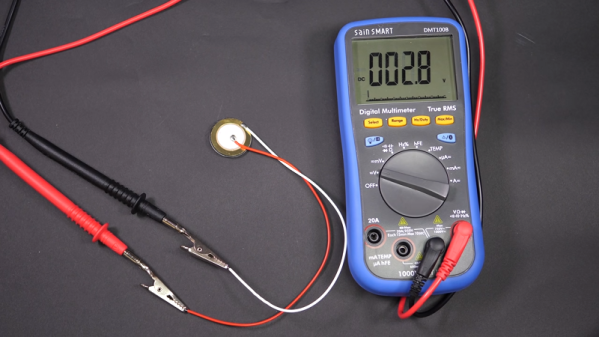

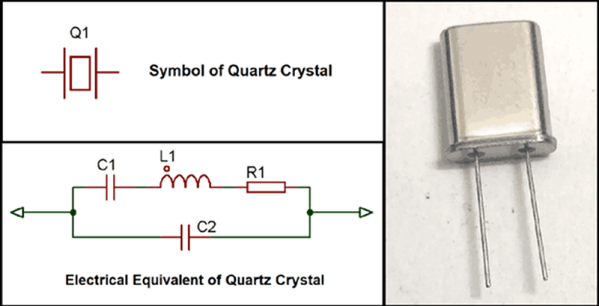

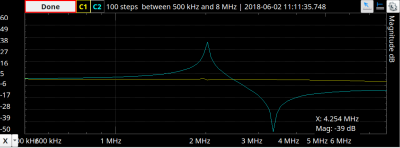

This morning Joe Grand — badge maker for this year and many of the glory years of hardware badges up through DC18 — took the stage to share his story of conceptualizing, prototyping, and shepherding the manufacturing process for 28,500 badges. Imagine the pressure of delivering a delightful concept, on-time, and on budget… well, almost on budget. During the talk he spilled the beans on the quartz crystal hanging off the front side of every PCB.

Continue reading “DEF CON 27: The Badge Talk; Or That One Time Joe Grand Sourced 30,000 Gemstones”