One way to keep things tiny is to make a system with cartridges where the brain lives on each cartridge instead of the platform itself. [Michael]’s Epic Minimalist Entertainment System (EMES) is one of those, and boy, is it tiny. EMES makes use of the ATtiny10, and they don’t get much AT-tinier than that.

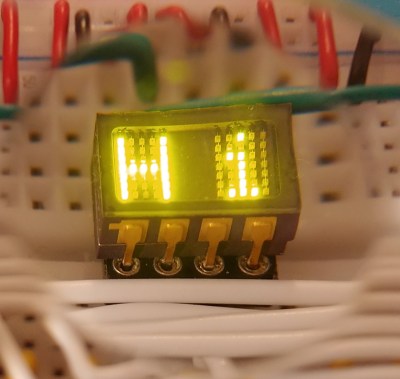

This nearly microscopic console uses an equally Lilliputian display — a Plessey GPD340 vintage LED display, in fact. (Check out [Michael]’s reverse engineering project if you want to play around with these.) There are four ultra-small buttons for control and a buzzer for sound.

This nearly microscopic console uses an equally Lilliputian display — a Plessey GPD340 vintage LED display, in fact. (Check out [Michael]’s reverse engineering project if you want to play around with these.) There are four ultra-small buttons for control and a buzzer for sound.

Now, the ATtiny10 is an 8Mhz microcontroller with 1KB of flash and 32 bytes of RAM. It has an 8-bit ADC and a somewhat surprisingly high four GPIO pins. But of course, that’s not enough. Not with the display, the four buttons, and the buzzer, so [Michael] had to come up with a way to multiplex everything to four GPIOs.

PB0 is shared between the buttons and the display’s serial data input. PB1 cleverly outputs the same PWM for both the brightness control and the buzzer. When the buzzer is needed, [Michael]’s code switches to a lower frequency and adjusts the duty cycle of the display to keep it readable. PB2 and 3 are serial clock inputs for the two display halves. Be sure to check it out the heated PONG action in the video after the break!

There’s still a little bit of time to enter the 2024 Tiny Games Contest! You have until Tuesday, September 10th, so head on over to Hackaday.IO and get started!

Continue reading “2024 Tiny Games Contest: An Epic Minimalist Entertainment System, Indeed”