[Zibartas] recently created wearable helmets from the game Starfield that look fantastic, and we’re happy to see that he created a video showcasing the whole process of design, manufacture, and assembly. The video really highlights just how much good old-fashioned manual work like sanding goes into getting good results, even in an era where fancy modern equipment like 3D printing is available to just about anyone.

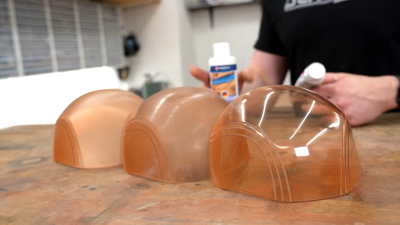

The visor, for example, is one such example. The usual approach to making a custom helmet visor (like for Daft Punk helmet builds) is some kind of thermoforming. However, the Starfield helmet visors were poor candidates due to their shape and color. [Zibartas]’s solution was to 3D print the whole visor in custom-tinted resin, followed by lots and lots of sanding and polishing to obtain a clear and glassy-smooth end product.

A lot of patient sanding ended up being necessary for other reasons as well. Each helmet has a staggering number of individual parts, most of which are 3D printed with resin, and these parts didn’t always fit together perfectly well.

[Zibartas] also ended up spending a lot of time troubleshooting an issue that many of us might have had an easier time recognizing and addressing. The helmet cleverly integrates a faux-neon style RGB LED strip for internal lighting, but the LED strip would glitch out when the ventilation fan was turned on. The solution after a lot of troubleshooting ended up being simple decoupling capacitors, helping to isolate the microcontrollers built into the LED strip from the inductive load of the motors.

What [Zibartas] may have lacked in the finer points of electronics, he certainly makes up for in practical experience when it comes to wearable pieces like these. The helmets look solid but are in fact full of open spaces and hollow, porous surfaces. This makes them more challenging to design and assemble, but it pays off in spades when worn. The helmets not only look great, but allow a huge amount of airflow. This along with the fans makes them comfortable to wear as well as prevents the face shield from misting up from the wearer’s breathing. It’s a real work of art, so check out the build video, embedded just below.

Continue reading “See The Hands-on Details Behind Stunning Helmet Build”