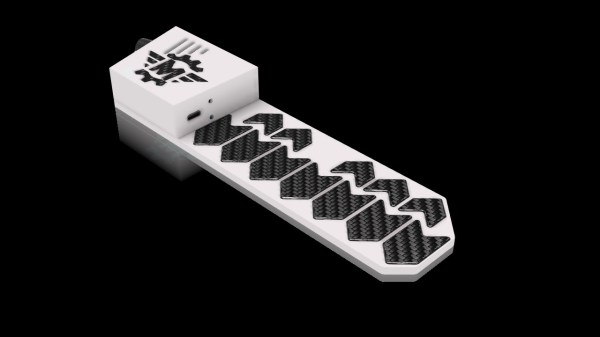

A good amount of hacks can be done with off-the-shelf hardware – what’s more, it’s usually available all over the world, which means your hacks are easier to build for others, too. Say, you’ve built something around a commonly available portable router, through the magic of open-source software. How do you make the fruits of your labour easy to install for your friends and blog readers? Well, you might want to learn a thing or two from [Albert], who shows us a portable DLNA server built around a GL-MT300N-V2 pocket router.

[Albert]’s blog post is a tutorial on setting it up, with a pre-compiled binary image you can flash onto your router. Flash it, prepare a flash drive with your media files, connect to the WiFi network created by the router, run the VLC player app, and your media library is with you wherever you go.

Now, a binary image is good, but are you wondering how it was made, and how you could achieve similar levels of user-friendliness in your project? Of course, here’s the GitHub repository with OpenWRT configuration files used to build this image, and build instructions are right there in the README. If you ever needed a reference on how to make commonly available OpenWRT devices do your bidding automagically, this is it.

This is an elegant solution to build an portable DLNA server that’s always with you on long rides, and, think of it, it handily beats a typical commercialized alternative, at a lower cost. Want software upgrades? Minor improvements and fixes? Security patches? Everything is under your control, and thanks to the open-source nature of this project, you have a template to follow. There won’t always be a perfectly suited piece of hardware on the market, of course, as this elegant dual-drive Pi-based NAS build will attest.