We’re now accustomed to hearing, “We’re all special in our own unique ways.” But what if we weren’t really aren’t all that unique? Many people think there are no more than two political opinions, maybe a handful of religious beliefs, and certainly no more than one way to characterize a hack. But despite this controversy in other aspects as life, at least we can all rely on the uniqueness of our individual names. Or can you?

You ever thought there were too many people named [insert name here]? Well, [Nicole] thought there were too many people who shared her name in her home country of Belgium and decided to make an art piece out of it.

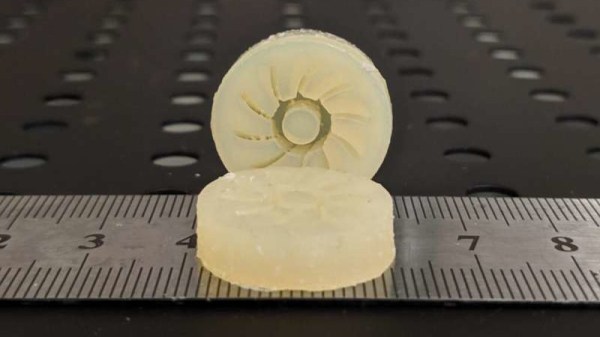

She was able to find data on the first names of people in Belgium and wrote a Python script…er…used Excel to find the number of Nicoles in each zip code. She then created a 3D map of Belgium divided into each province with the height of each province proportional to the number of Nicoles in that area. A pretty simple print job that any standard 3D printer can probably do these days.

Not much of a “do something” hack, but could make for a cool demotivational ornament that will constantly remind us just how unique we really are.

Happy hacking!