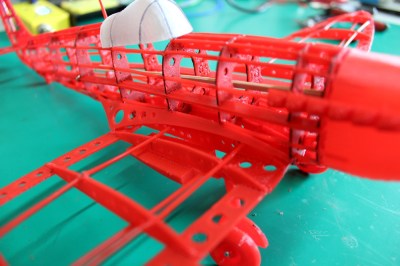

Not long ago, photogrammetry — the process of stitching multiple photographs taken from different angles into a 3D whole — was hard stuff. Nowadays, it’s easy. [Mikolas Zuza] over at Prusa Printers, has a guide showing off cutting edge open-source software that’s not only more powerful, but also easier to use. They’ve also produced a video, which we’ve embedded below.

Basically, this is a guide to using Meshroom, which is based on the AliceVision photogrammetry framework. AliceVision is a research platform, so it’s got tremendous capability but doesn’t necessarily focus on the user experience. Enter Meshroom, which makes that power accessible.

Meshroom does all sorts of cool tricks, like showing you how the 3D reconstruction looks as you add more images to the dataset, so that you’ll know where to take the next photo to fill in incomplete patches. It can also reconstruct from video, say if you just walked around the object with a camera running.

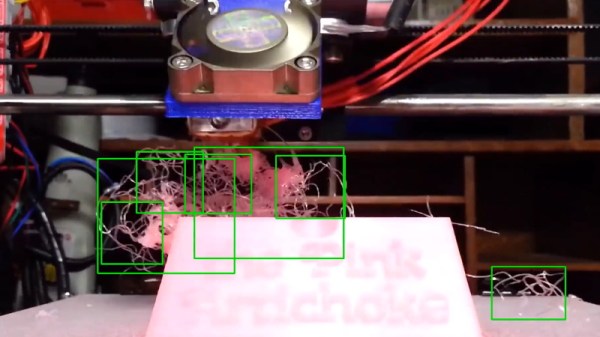

The final render is computationally intensive, but AliceVision makes good use of a CUDA on Nvidia graphics cards, so you can cut your overnight renders down to a few hours if you’ve got the right hardware. But even if you have to wait for the results, they’re truly impressive. And best of all, you can get started building up your 3D model library using nothing more than that phone in your pocket.

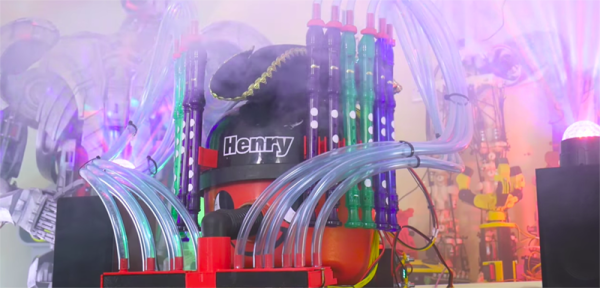

If you want to know how to use the models that come out of photogrammetry, check out [Eric Strebel]’s video. And if all of this high-tech software foolery is too much for you, try a milk-based 3D scanner.

Continue reading “Get Great 3D Scans With Open Photogrammetry”