The Rigol DHO800 and DHO900 series use Android underneath, and as you might expect, this makes them easier to hack. A case in point: [VoltLog] demonstrates that you can add WiFi to the scope using a cheap USB WiFi adapter. This might seem like a no-brainer on the surface, but because the software doesn’t know about WiFi, there are a few minor hoops to jump through.

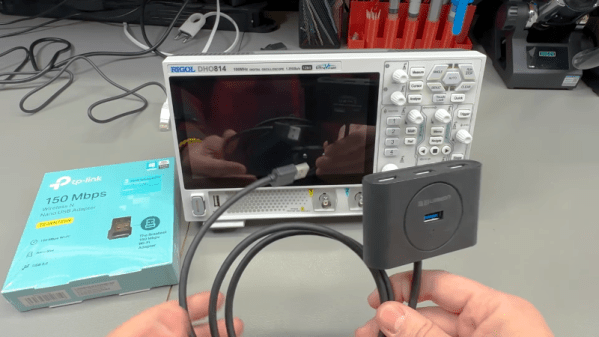

The first issue is that you need a WiFi adapter the built-in OS already knows how to handle. The community has identified at least one RTL chipset that works and it happens to be in the TP-Link TL-WN725N. These are old 2.4 GHz only units, so they are widely available for $10 or less.

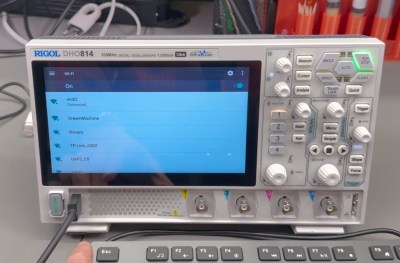

But even with the correct hardware, the scope doesn’t have any menus to configure the WiFi interface. To solve that, you need to temporarily use a USB hub and a USB keyboard. Once you have everything plugged in, you can use the Super + N keyboard shortcut to open up the Android notification bar, which is normally hidden. Once you’ve setup the network connection, you won’t need the keyboard anymore.

But even with the correct hardware, the scope doesn’t have any menus to configure the WiFi interface. To solve that, you need to temporarily use a USB hub and a USB keyboard. Once you have everything plugged in, you can use the Super + N keyboard shortcut to open up the Android notification bar, which is normally hidden. Once you’ve setup the network connection, you won’t need the keyboard anymore.

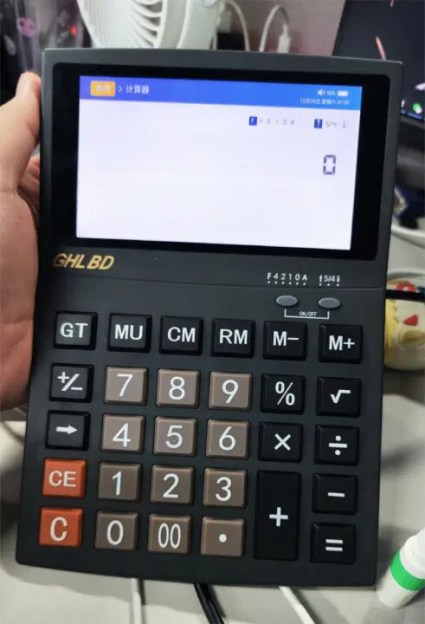

Or maybe not — it turns out the keyboard does allow you to change a few other things. For example, [VoltLog] used it to increase the screen brightness more than the default maximum setting.

The only other issue appears to be that the scope shows it is disconnected even when connected to WiFi. That doesn’t seem to impact operation, though. Of course, you could use a WiFi to Ethernet bridge or even an old router, but now you have a cable, a box, and another power cord to deal with. This solution is neat and clean. You bet we’ve already ordered a TP-Link adapter!

WiFi scopes are nothing new. We suspect Rigol didn’t want to worry about interference and regulatory acceptance, but who knows? Besides, it is fun to add WiFi to wired devices.

Now, there’s caveats. [extrowerk] points out that you should buy the modem with the appropriate LTE bands for your country – and that’s not the only thing to watch out for. A friend of ours recently obtained a visually identical modem; when we got news of this hack, she disassembled it for us – finding out that it was equipped with a far more limited CPU, the MDM9600. That is an LTE modem chip, and its functions are limited to performing USB 4G stick duty with some basic WiFi features. Judging by a popular mobile device reverse-engineering forum’s

Now, there’s caveats. [extrowerk] points out that you should buy the modem with the appropriate LTE bands for your country – and that’s not the only thing to watch out for. A friend of ours recently obtained a visually identical modem; when we got news of this hack, she disassembled it for us – finding out that it was equipped with a far more limited CPU, the MDM9600. That is an LTE modem chip, and its functions are limited to performing USB 4G stick duty with some basic WiFi features. Judging by a popular mobile device reverse-engineering forum’s