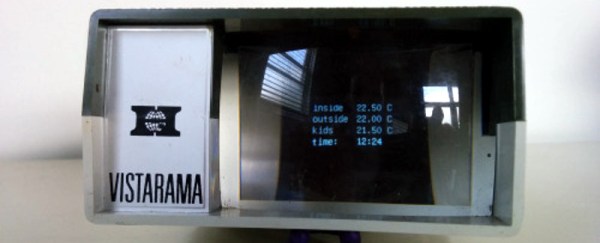

Sometimes when browsing the websites of our global hackspace community you notice a project that’s attractive not necessarily because of what it does or its technology but because of its presentation. So it is with the subject of this article, [Kris] needed a house temperature monitor and found a 1960s slide viewer made an excellent choice for its housing.

The monitor itself is a fairly straightforward Arduino build using a couple of DS18B20 1-wire temperature sensors and a real-time-clock module and displaying their readings on a small OLED screen. Its code can be found on this mailing list thread if you are interested. The display presented a problem as it needed to be reasonably large, yet fairly dim so it could be read at night without being bright enough to interrupt sleep.

A variety of projection techniques were tried, involving lenses from a projection clock, a magnifying glass, and a Google Cardboard clone. Sadly none of these lenses had the required focal length. Eventually the slide viewer was chosen because it was pointed out that the OLED screen was about the same size as a photographic slide.

Slide viewers are part of the familiar ephemera of the analog era that most people over 60 may still have taking up drawer space somewhere but may well be completely alien to anyone under about 30. They were a magnification system packaged up into a console usually styled to look something like a small portable TV of the day, and different models had built-in battery lights, or collected ambient light with a mirror. The screen was usually a large rectangular lens about 100mm(4″) diagonal.

[Kris]’s Vistarama slide viewer came via eBay. It’s not the smallest of viewers, other models folded their light paths with mirrors, however the extra space meant that the Arduino fit easily. The OLED was placed where the slide would go, and its display appeared at just the right magnification and brightness. Job done, and looking rather stylish!

We’ve not featured a slide viewer before here at Hackaday, though we did recently feature a similar hack on an Ikea toy projector. We have however featured more than one digital conversion on a classic slide projector using LCD screens in place of the slide.

Via Robots and Dinosaurs makerspace, Sydney.