With a new Matrix movie now in cinemas, we’ve all been reminded of those screensavers that were just the coolest thing ever when the original film dropped in 1999. [en0b] decided to recreate the classic “digital rain” effect on the Raspberry Pi Pico, using up all the little microcontroller’s storage in the process.

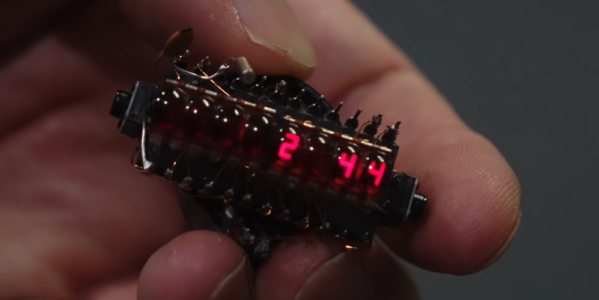

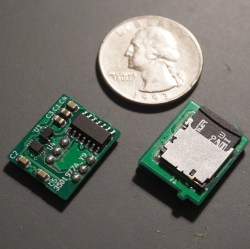

Rather than rely on existing graphics libraries, [en0b] set about using a high-quality GIF for the animation. The original file was 8 MB, which was far too big to fit on the Pico. After some finagling in an image editor and with the help of a custom Python script, however, [en0b] managed to fit the 127-frame animation at 240 x 135 resolution into the 2 MB Flash onboard the chip. With the microcontroller hooked up to the 1.14″ IPS “Pico Display” from Pimoroni, the final looks great and faithfully recreates the aesthetic seen in the film.

[en0b]’s technique could reliably be used for displaying any GIF that you can cut down to 14 to 16 colors without losing too much quality. It’s not the world’s highest-end graphics format, but it does the job for little animations like these.

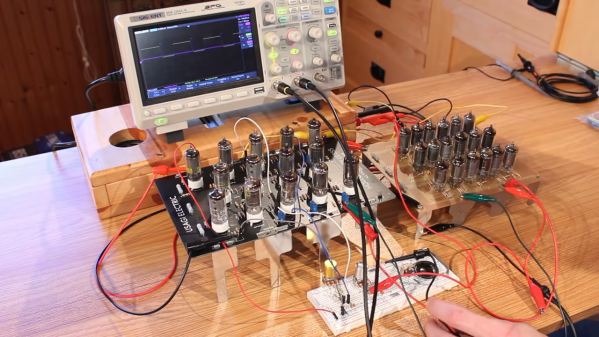

We’ve seen similar builds before too, using more heavy-duty hardware to build a magic 8-ball in much the same way. Meanwhile, if you’ve got your own neat little GIF hacks or Pico projects, don’t hesitate to send them in!