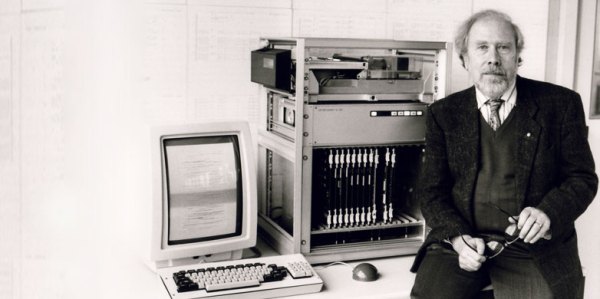

Although perhaps not as much of a household name as other pioneers of last century’s rapid evolution of computer hardware and the software running on them, Niklaus Wirth’s contributions puts him right along with other giants. Being a very familiar face both in his native Switzerland at the ETH Zurich university – as well as at Stanford and other locations around the world where computer history was written – Niklaus not only gave us Pascal and Modula-2, but also inspired countless other languages as well as their developers.

Sadly, Niklaus Wirth passed away on January 1st, 2024, at the age of 89. Until his death, he continued to work on the Oberon programming language, as well as its associated operating system: Oberon System and the multi-process, SMP-capable A2 (Bluebottle) operating system that runs natively on x86, X86_64 and ARM hardware. Leaving behind a legacy that stretches from the 1960s to today, it’s hard to think of any aspect of modern computing that wasn’t in some way influenced or directly improved by Niklaus.

Continue reading “Remembering Niklaus Wirth: Father Of Pascal And Inspiration To Many”