The Baader-Meinhof effect is the common name for what scientists call frequency illusion. Suppose you are watching Star Trek’s Christopher Pike explain how he makes pasta mama, and you’ve never heard of it before. Immediately after that, you’ll hear about pasta mama repeatedly. You’ll see it on menus. Someone at work will talk about having it at Hugo’s. Here’s the thing. Pasta mama was there all along (and, by the way, delicious). You just started noticing it. We sometimes wonder if that’s the deal with Morse code. Once you know it, it seems to show up everywhere.

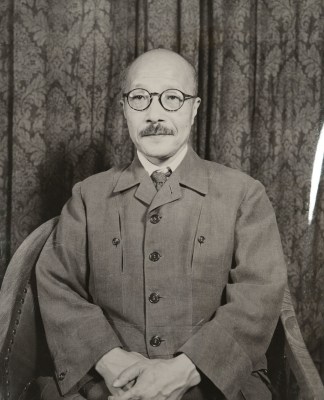

One of the strangest places we’ve ever heard of Morse code appearing is the infamous case of Tojo’s teeth. If you don’t remember, General Hideki Tojo was one of the main “bad guys” in the Pacific part of World War II. In particular, he is thought to have approved the attack on Pearl Harbor, which started the American involvement in the war globally. Turns out, Tojo would be inextricably tied to Morse code, but he probably didn’t realize it.

The Honorable Attempt

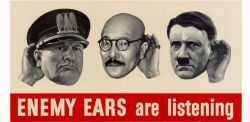

At the end of the war, the US military had a list of people they wanted to try, and Tojo was near the top of their list of 40 top-level officials. As prime minister of Japan, he had ordered the attack that brought the US into the war. He remained prime minister until 1944, when he resigned, but the US had painted him as the face of the Japanese enemy. Often shown in caricature along with Hitler and Mussolini, Tojo was the face of the Japanese war machine to most Americans.

When Americans tried to arrest him, though, he shot himself. However, his suicide attempt failed. Reportedly, he apologized to the American medics who resuscitated him for failing to kill himself. Held in Sugamo Prison awaiting a trial, he requested a dentist to make him a new set of dentures so he could speak clearly during the trial.

Continue reading “Gen Tojo’s Teeth: Morse Code Shows Up In The Strangest Places”