The Quickshot II was released by Spectravideo in 1983 for the Commodore 64 and compatible systems, with the Quickshot II Plus following the next year. After decades of regular use, it’s quite understandable that these old-timers may be having some functional issues, but as long as the plastic parts are still good, [Stephan Eckweiler]’s replacement PCBs may be just the thing that these joysticks need to revitalize them for another few decades.

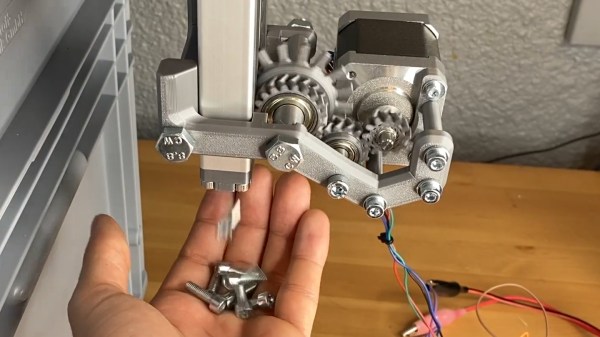

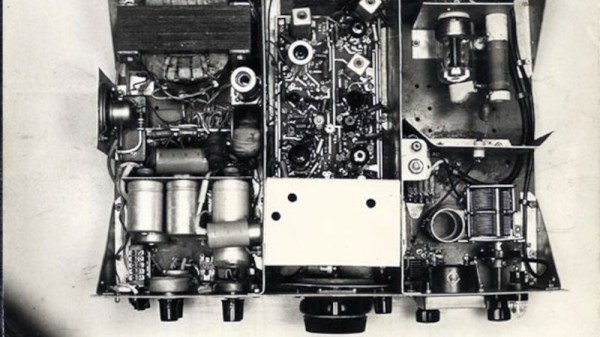

What may be a matter of taste is that these replace the nice tactile clicky switches on the QS II Plus with SMD push buttons, but compared to the stamped metal ‘button’ construction of the original QS II, the new board is probably a major improvement. As for the BOM, it features two ICs: a 74LS00 latch and NE555 timer, along with the expected stack of passives and switches, both through-hole and SMD.

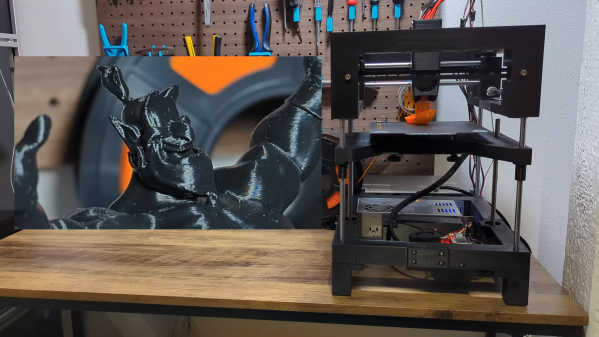

The PCB contains break-off boards for the switches within the joystick itself, requiring a bit of wiring to be run to the main PCB before soldering on the DE-9 connector and connecting the joystick for a test run to a Commodore 64. All one needs now is a 3D printable enclosure version to create more QS II joysticks for some multiplayer action.