The list of bad legislation relating to the topic of encryption and privacy is long and inglorious. Usually, these legislative stinkers only affect those unfortunate enough to live in the country that passed them. Still, one upcoming law from the British government should have us all concerned. The Online Safety Bill started as the usual think-of-the-children stuff, but as the EFF notes, some of its proposed powers have the potential to undermine encryption worldwide.

At issue is the proposal that services with strong encryption incorporate government-sanctioned backdoors to give the spooks free rein to snoop on communications. We imagine that this will be of significant interest to some of the world’s less savoury regimes, a club we can’t honestly say the current UK government doesn’t seem hell-bent on joining. The Bill has had a tumultuous passage through the Lords, the UK upper house, but PM Rishi Sunak’s administration has proved unbending.

If there’s a silver lining to this legislative train wreck, it’s that many of the global tech companies are likely to pull their products from the UK market rather than comply. We understand that UK lawmakers are partial to encrypted online messaging platforms. Thus, there will be poetic justice in their voting once more for a disastrous bill with the unintended consequence of taking away something they rely on.

Header image: DaniKauf, CC BY-SA 3.0.

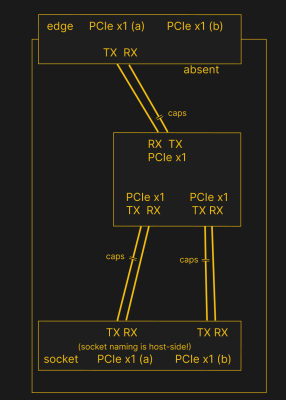

PCIe needs TX pairs connected to RX on another end, like UART – and this is non-negotiable. Connectors will use host-side naming, and vice-versa. As the diagram demonstrates, we connect the socket’s TX to chip’s RX and vice-versa; if we ever get confused, the laptop schematic is there to help us make things clear. To sum up, we only need to flip the names on the link coming to the PCIe switch, since the PCIe switch acts as a device on the card; the two links from the switch go to the E-key socket, and for that socket’s purposes, the PCIe switch acts as a host.

PCIe needs TX pairs connected to RX on another end, like UART – and this is non-negotiable. Connectors will use host-side naming, and vice-versa. As the diagram demonstrates, we connect the socket’s TX to chip’s RX and vice-versa; if we ever get confused, the laptop schematic is there to help us make things clear. To sum up, we only need to flip the names on the link coming to the PCIe switch, since the PCIe switch acts as a device on the card; the two links from the switch go to the E-key socket, and for that socket’s purposes, the PCIe switch acts as a host.