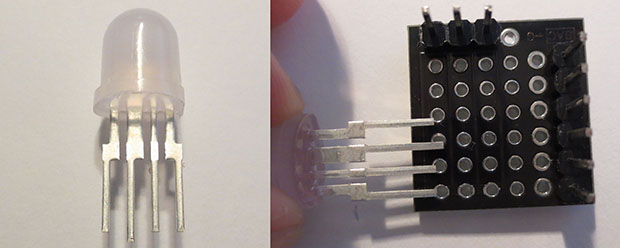

What you see above is a cordwood circuit, an interesting circuit construction technique from before the days of integrated circuits. The circuit consists of two circuit boards arranged parallel to each other with components holding them apart. This was, for its day, the densest circuit construction technique, used in everything from late 50s aerospace tech to huge computers that filled rooms.

The folks over at Boldport have a love for interesting PCBs and are apparently aficionados of antiquated tech, leading them to create their own cordwood circuit. Here’s the best part: it’s a kit, without assembly instructions.

The cordwood puzzle assembles into a bunch of LEDs that will light up when power is applied. Not much, but there’s a few FETs in there that allow you to control them all individually with a microcontroller. The real fun is trying to assemble the kit: both sides of the cordwood circuit are identical, meaning there’s going to be holes that aren’t meant to be filled, components that will need to be soldered, and most likely a bit of swearing.

Still, this is an exceptionally small circuit for something using this construction technique. If you know of a denser and more modern cordwood circuit out there, leave a note in the comments. If you want to know what the kit looks like when it’s built, [Phil Wright] has your back.