It’s basically a lightsaber. Except smaller. And with an invisible blade. And cold to the touch. But other than that, this homebrew cold plasma torch (YouTube, embedded below) is just like the Jedi’s choice in elegant weaponry.

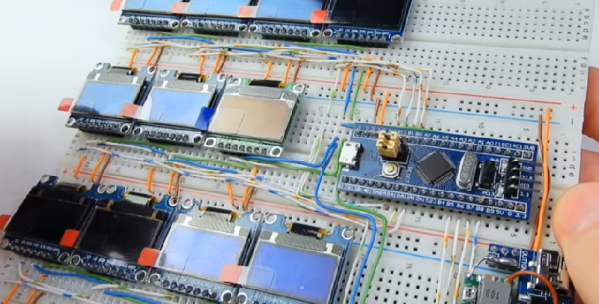

Perhaps we shouldn’t kid [Justin] given how hard he worked on this project – seventeen prototypes before hitting on the version seen in the video below – but he himself notes the underwhelming appearance of the torch without the benefit of long-exposure photography. That doesn’t detract from how cool this build is, pun intended. As [Justin] explains, cold plasma or non-equilibrium plasma is an ionized stream of gas where the electron temperature is much hotter than the temperature of the heavier, more thermally conductive species in the stream. It’s pretty common stuff, seen commercially in everything from mercury vapor lamps to microbial sterilization.

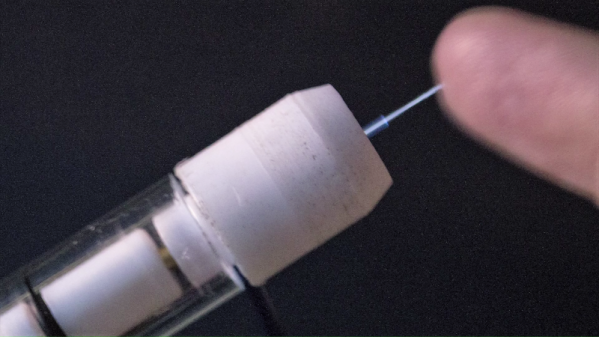

It’s the latter use that piqued [Justin]’s interest and resulted in a solid year of prototyping before dialing in a design using a flyback transformer to delivery the high voltage to a stream of argon flowing inside a capillary tube. The quartz tube acts as a dielectric that keeps electrons from escaping and allows argon to be ionized and wafted gently from the tube before it can reach thermal equilibrium. The result is a faint blue glowing flame that’s barely above room temperature but still has all the reactive properties of a plasma. The video shows all the details of construction and shows the torch in action.

Hats off to [Justin] for sticking with a difficult build and coming through it with an interesting and useful device. We’ve no doubt he’ll put it to good use in his DIY biohacking lab in the coming months.

Continue reading “Cold Plasma Torch Produces A Cleansing Flame That Never Consumes”