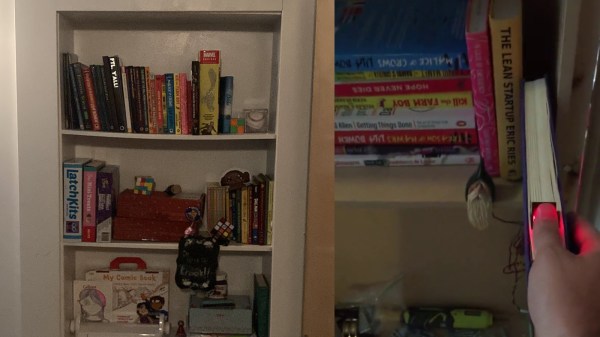

What is it that compels us about a secret door? It’s almost as if the door itself and the promise of mystery is more exciting than whatever could lay beyond. In any case, [Scott Monaghan] is a lover of the form, and built his own secret door hidden in a bookshelf, as all good secret doors should be.

The door is activated by pulling down on the correct book. This then reveals a fingerprint scanner. Upon presenting the right digit, the door will elegantly swing open to reveal the room beyond. Secret door experts will note there’s an obvious tell due to the light spilling through the cracks, however [Scott] reports that the finishing stages of the build solved this issue. The door was also fitted with a manual release for easier daily use.

Details are light, but the basics are all there. Really all you need is a cheap hardware store door opener, a secret activation lever or authentication method, and a well-hinged bookcase to achieve this feat yourself. We’ve seen some other great secret doors before, too. Video after the break.

Continue reading “Secret Bookshelf Door Uses Hidden Fingerprint Scanner”