What is it about solenoids that makes people want to make music with them? Whatever it is, we hope that solenoids never stop inspiring people to make instruments like [CamsLab]’s copper pipe auto-glockenspiel.

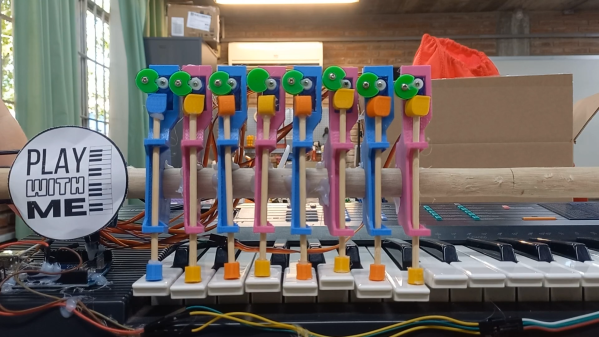

At first, [CamsLab] thought of striking glasses of water, but didn’t like the temporary vibe of a setup like that. They also considered striking piano keys, but thought better of it when considering the extra clicking sound that the solenoids would make, plus it seemed needlessly complicated to execute. So [CamsLab] settled on copper pipes.

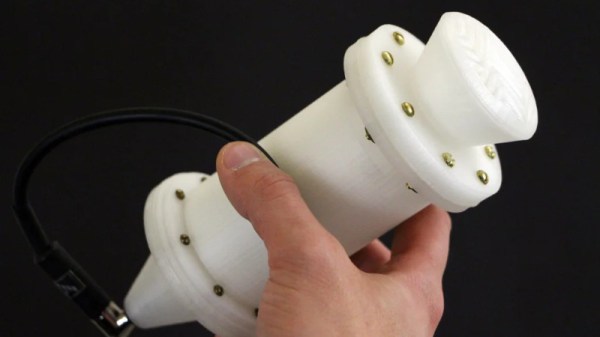

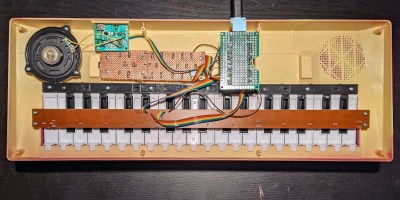

That in itself was a challenge as [CamsLab] had to figure out just the right lengths to cut each pipe in order to produce the desired pitch. Fortunately, they started with a modest 15-pipe glockenspiel as a proof of concept. However, the most challenging aspect of this project was figuring out how to mount the pipes so that they are close enough to the solenoids but not too close, and weren’t going to move over time. [CamsLab] settled on fishing line to suspend them with a 3D-printed frame mounted on extruded aluminium. The end result looks and sounds great, as you can hear in the video after the break.

Of course, there’s more than one way to auto-glockenspiel. You could always use servos.

Continue reading “Arduino Auto-Glockenspiel Looks Proper In Copper”