When it comes to finding what direction a radio signal is coming from, the best and cheapest way to accomplish the task is usually a Yagi and getting dizzy. There are other methods, and at Shmoocon this last weekend, [Michael Ossmann] and [Schuyler St. Leger] demonstrated pseudo-doppler direction finding using cheap, off-the-shelf software defined radio hardware.

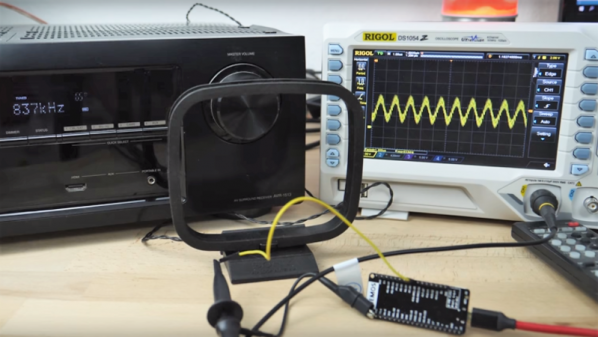

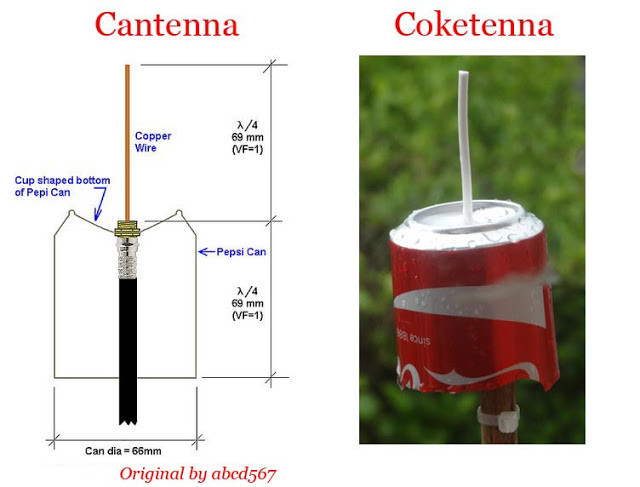

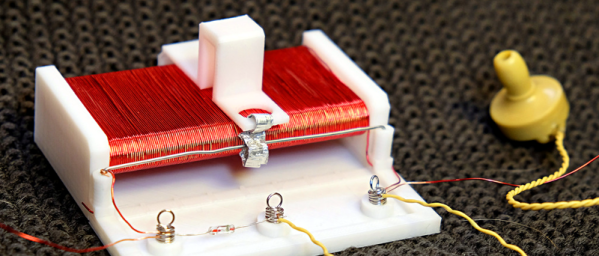

The hardware for this build is, of course, the HackRF, but this pseudo-doppler requires antenna switching. That means length-matched antennas, and switching antennas without interrupts or other CPU delays. This required an add-on board for the HackRF dubbed the Opera Cake. This board is effectively an eight-input antenna switcher using the state configurable timer found in the LPC43xx found on the HackRF.

The key technique for pseudo-doppler is basically switching between an array of antennas mounted in a circle. By switching through these antennas very, very quickly — on the order of hundreds of thousands of times per second — you can measure the Doppler shift of a transmitter.

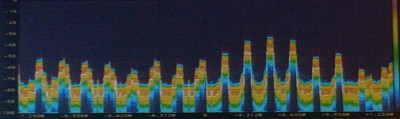

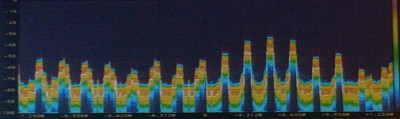

However, teasing out a distinct signal from a bunch of antennas virtually whizzing about isn’t exactly easy. If you look at what the HackRF an Opera Cake receive on a waterfall display, you’ll find a big peak around where you expect, and copies of that signal trailing off, separated by whatever your antenna switching frequency is. This was initially a problem for [Schuyler] and [Ossmann]’s experiments. Spinning the antennas at 20 kHz meant there was only 20 kHz difference in these copies, resulting in a mess that can’t be decoded. The solution was to virtually spin these antennas much faster, resulting in more separation, and a clean signal.

However, teasing out a distinct signal from a bunch of antennas virtually whizzing about isn’t exactly easy. If you look at what the HackRF an Opera Cake receive on a waterfall display, you’ll find a big peak around where you expect, and copies of that signal trailing off, separated by whatever your antenna switching frequency is. This was initially a problem for [Schuyler] and [Ossmann]’s experiments. Spinning the antennas at 20 kHz meant there was only 20 kHz difference in these copies, resulting in a mess that can’t be decoded. The solution was to virtually spin these antennas much faster, resulting in more separation, and a clean signal.

There are significant challenges when it comes to finding the direction of modern radio targets. Internet of Things things sometimes have very short packet duration, modulation interferes with antenna rotation, and packet detection must maintain the phase. That said, is this technique actually able to find the direction of IoT garbage devices? Yes, the demo on stage was simply finding the direction of one of the wireless microphones for the talk. It mostly worked, but the guys have some ideas for the future that would make this technique work a little better. They’re going to try phase demodulation instead of only frequency-based demodulation. They’re also going to try asymmetric antenna arrays and pseudorandom antenna switching. With any luck, this is going to become an easy and cheap way to do pseudo-doppler direction finding, all enabled by a few dollars in hardware and a laser-cut jig to hold a few antennas.