Back in 2015, European Space Agency (ESA) astronaut Tim Peake brought a pair of specially equipped Raspberry Pi computers, nicknamed Izzy and Ed, onto the International Space Station and invited students back on Earth to develop software for them as part of the Astro Pi Challenge. To date, more than 50,000 young people have had their code run on one of the single-board computers; making them arguably the most popular, and surely the most traveled, Raspberry Pis in the solar system.

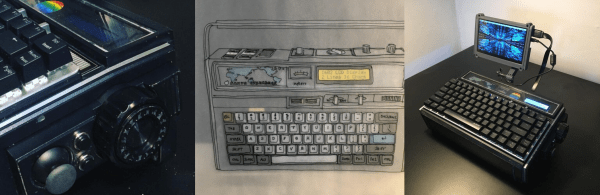

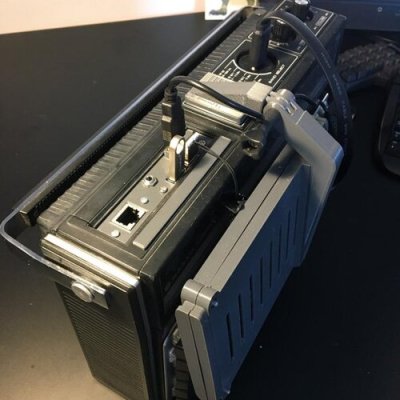

While Izzy and Ed are still going strong, the ESA has decided it’s about time these veteran Raspberries finally get the retirement they’re due. Set to make the journey to the ISS in December aboard a SpaceX Cargo Dragon, the new Astro Pi MK II hardware looks quite similar to the original 2015 version at first glance. But a peek inside its 6063-grade aluminium flight case reveals plenty of new and improved gear, including a Raspberry Pi 4 Model B with 8 GB RAM.

While Izzy and Ed are still going strong, the ESA has decided it’s about time these veteran Raspberries finally get the retirement they’re due. Set to make the journey to the ISS in December aboard a SpaceX Cargo Dragon, the new Astro Pi MK II hardware looks quite similar to the original 2015 version at first glance. But a peek inside its 6063-grade aluminium flight case reveals plenty of new and improved gear, including a Raspberry Pi 4 Model B with 8 GB RAM.

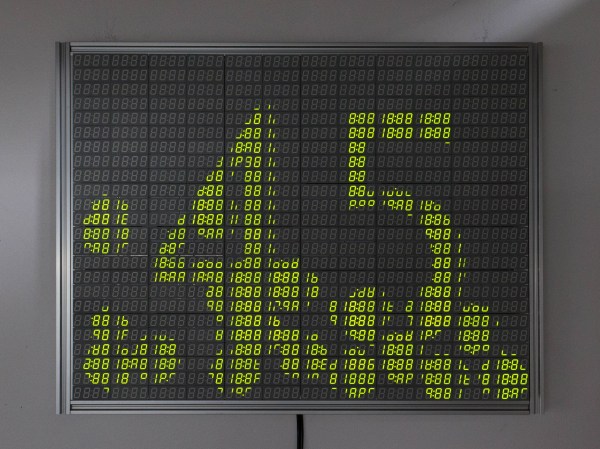

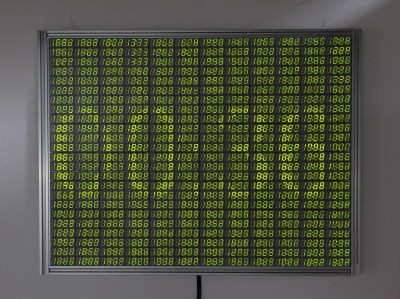

The beefier hardware will no doubt be appreciated by students looking to push the envelope. While the majority of Python programs submitted to the Astro Pi program did little more than poll the current reading from the unit’s temperature or humidity sensors and scroll messages for the astronauts on the Astro Pi’s LED matrix, some of the more advanced projects were aimed at performing legitimate space research. From using the onboard camera to image the Earth and make weather predictions to attempting to map the planet’s magnetic field, code submitted from teams of older students will certainly benefit from the improved computational performance and expanded RAM of the newest Pi.

As with the original Astro Pi, the ESA and the Raspberry Pi Foundation have shared plenty of technical details about these space-rated Linux boxes. After all, students are expected to develop and test their code on essentially the same hardware down here on Earth before it gets beamed up to the orbiting computers. So let’s take a quick look at the new hardware inside Astro Pi MK II, and what sort of research it should enable for students in 2022 and beyond.

Continue reading “Astro Pi Mk II, The New Raspberry Pi Hardware Headed To The Space Station”