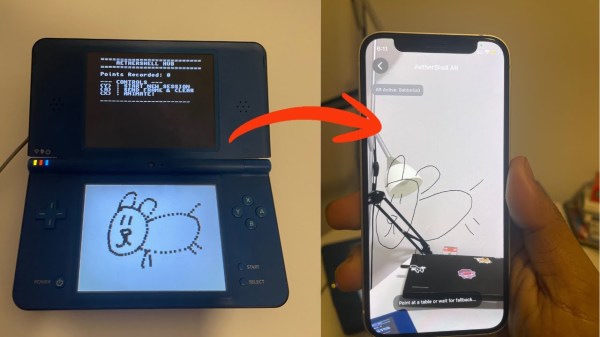

[Bhaskar Das] has been tinkering with one of Nintendo’s more obscure handhelds, the DSi. The old-school console has been given a new job as part of an augmented reality app called AetherShell.

The concept is straightforward enough. The Nintendo DSi runs a small homebrew app which lets you use the stylus to make simple line drawings on the lower touchscreen. These drawings are then trucked out wirelessly as raw touch data via UDP packets, and fed into a Gemini tool geometric reconstruction script written in Python which transforms them into animation frames. A Gemini tool is used to classify what the drawings are in order for a future sound effects upgrade, too. These are then sent to an iPhone app, which uses ARKit APIs and the phone’s camera to display the animations embedded into the surrounding environment via augmented reality.

One might question the utility of this project, given that the iPhone itself has a touch screen you can draw on, too. It’s a fair question, and one without a real answer, beyond the fact that sometimes it’s really fun to play with an old console and do weird things with it. Plus, there just isn’t enough DSi homebrew out in the world. We love to see more.

Continue reading “Augmented Reality Project Utilizes The Nintendo DSi”

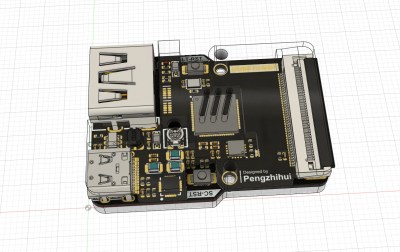

The new display could have used the DSI (Display Serial Interface) adapter, or the small connector on the Pi that is not the camera connector. DSI displays are purpose-built for specific devices, though, and aren’t something that would or should be used in a device that will be manufactured for years to come. The best solution, and the design the Raspberry Pi foundation chose to go with, is a DPI display and an adapter that converts the Pi’s DSI output to something the display can understand.

The new display could have used the DSI (Display Serial Interface) adapter, or the small connector on the Pi that is not the camera connector. DSI displays are purpose-built for specific devices, though, and aren’t something that would or should be used in a device that will be manufactured for years to come. The best solution, and the design the Raspberry Pi foundation chose to go with, is a DPI display and an adapter that converts the Pi’s DSI output to something the display can understand.