A few years ago on a long flight across the North Atlantic, the perfect choice for a good read was iWoz, the autobiographical account of [Steve Wozniak]’s life. In it, he described his work replicating the wildly successful Pong video game and then that of designing the 8-bit Apple computers. A memorable passage involves his development of the Apple II’s color generation circuitry, which exploited some of the artifacts of the NTSC color system to produce a color display in a far simpler manner than might be expected. Now anyone seeking a connection with both Pong and the Apple II can have one of their very own if they have enough money because [Al Alcorn]’s Tektronix 465 oscilloscope is for sale. He’s the designer of the original Pong and used the instrument in its genesis, and then a few years later, he lent it to [Woz] for his work on the Apple II.

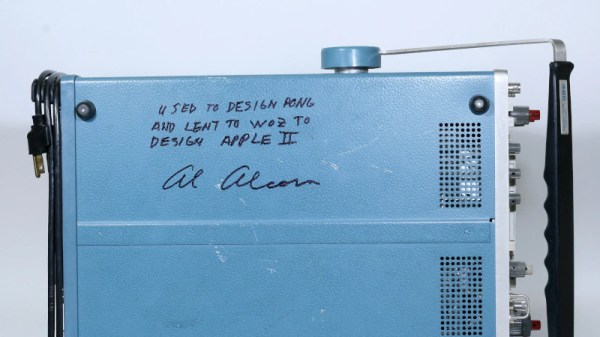

This may be the first time Hackaday has featured something from the catalogue of a rare book specialist, but if we’re being honest, for $135,000, it’s a little beyond the reach of a Hackaday scribe. The Tek 465 was a 100 MHz dual-trace model manufactured from 1972 to the early 1980s and, in its day, would have been a very desirable instrument indeed. This one is in pretty good condition with accompanying leads and manual and comes with a letter of authenticity and a hand-written annotation from [Al] himself on its underside. It can be seen up close in the video below the break.

As a ‘scope it’s an instrument many of us would still find useful today, but as the instrument which set in motion not one but two of the seminal moments of our craft, its historical importance can’t be overstated. We hope it will find its way into a museum or similar place where the story of those two developments can be told and that [Al] profits handsomely from its sale.

Continue reading “It’s A Humble ‘Scope, But It Changed Our World”