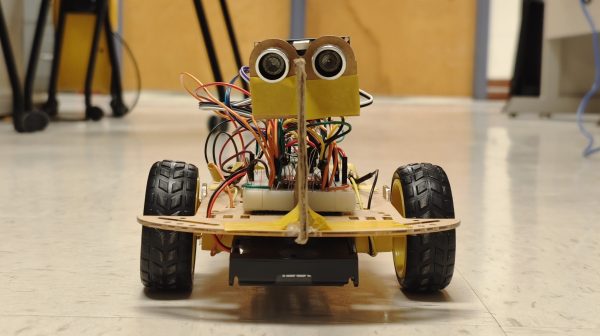

Typically, when we want to tell a robot where to go, we either pre-program a route or drive it around with some kind of gamepad or joystick controller. [Robotcus] decided to build a simple robot platform that drove around in response to voice commands instead.

The robot is based around a Raspberry Pi Zero, charged with instructing the motor controllers to drive the ‘bot around. The Pi Zero is also in charge of interpreting the voice commands via Google’s speech recognition tool. The ‘bot itself is a fairly simple design using brushed gearmotors for propulsion and a 3D-printed chassis to tie everything together.

The car is capable of understanding five commands – drive, turn left, turn right, go backwards, and “attack”. The last command simply activates a flipper from the robot’s former life as a battlebot. Things ran okay at first, but the Pi Zero was slow at processing commands. The wheels also had minimal traction. A full-fat Raspberry Pi solved the latter issue, while a new chassis provided better grip.

It’s a simple project, but one that taught [Robotcus] plenty about programming and building small robots in the process. Like so many learning experiences, it’s easy to see how the robot starts out flailing uselessly and eventually starts to perform as intended. It’s always nice to see that progression. Video after the break.

Continue reading “Voice Controlled Rover Follows Verbal Instructions To Get Around”