Modern technology is riddled with innovations that were initially inspired by the natural world. Velcro, bullet trains, airplanes, solar panels, and many other technologies took inspiration from nature to become what they are today. While some of these examples might seem like obvious places to look, scientists are peering into more unconventional locations for this transistor design which is both inspired by and made out of wood.

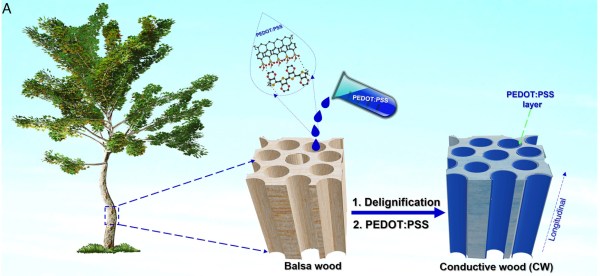

The first obvious hurdle to overcome with any electronics made out of wood is that wood isn’t particularly conductive, but then again a block of silicon needs some work before it reliably conducts electricity too. First, the lignin is removed from the wood by dissolving it in acetate, leaving behind mostly the cellulose structure. Then a conductive polymer is added to create a lattice structure of sorts using the wood cellulose as the structure. Within this structure, transistors can be constructed that function mostly the same as a conventional transistor might.

It might seem counterintuitive to use wood to build electronics like transistors, but this method might offer a number of advantages including sustainability, lower cost, recyclability, and physical flexibility. Wood can be worked in a number of ways once the lignin is removed, most notably when making paper, but removing the lignin can also make the wood relatively transparent as well which has a number of other potential uses.

Thanks to [Adrian] for the tip!