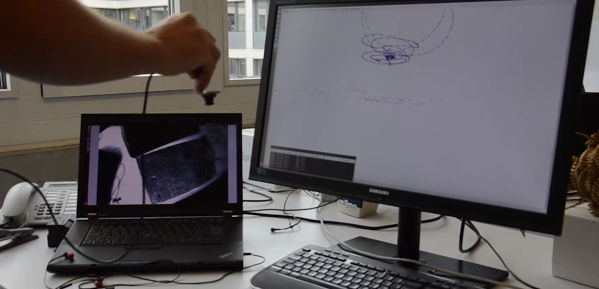

Let’s face it: 3-dimensional odometry can be a computationally expensive problem often requiring expensive 3D cameras and optimized algorithms that can be difficult to wrap our head around. Nevertheless, researchers continue to push the bounds of visual odometry forward each year. This past year was no exception, as [Christian], [Matia], and [Davide] have tipped the scale in terms of speed with an algorithm that can track itself in 3D in real time.

In the video (after the break), the landmarks are sparse, the motion to track is relentlessly jagged, but SVO, or Semi-Fast Visual Odometry [PDF warning], keeps tracking its precision with remarkable consistency, making use of “high frequency texture” as a reference. Several other implementations require two cameras or a depth camera variant, but not SVO. It uses a single camera with a high frame rate between 55 and 300 frames per second. Best of all, the trio at the University of Zürich have made their codebase open source and available as a package for ROS.