At one time, GoPro was valued at over eleven Billion dollars. It’s now on the verge of being a penny stock, because if surfers can make action cams and video editing software, anyone can. Action cams are everywhere, and one of the cheapest is the SQ11. It’s a rip-off of the Polaroid Cube, has a non-standard USB socket, a tiny battery, and the video isn’t that great. It only costs eight dollars, though, so [pixelk] decided to vastly expand the abilities of this cheap camera for a Hackaday Prize entry.

The major shortcoming of the SQ11 action cam is the tiny battery. Reportedly, it’s a 200 mAh battery, but the stated 1-2 hours of runtime bears no resemblance to reality. The solution to this problem, as with most things in life, is to throw some lithium cells at the problem.

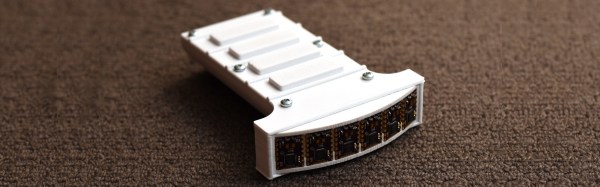

[pixelk] disassembled the SQ11 action cam and 3D printed a much longer enclosure meant to fit a single 18650 battery. There’s a protection circuit, so that’s fine, but there’s still a problem: the charging circuit in the camera is tailored for a 200 mAh battery — charging an 18650 cell would probably take a day. That’s no problem, because this enclosure leaves the battery removable, for easy recharging in an external device.

Does this make the SQ11 a good camera? Marginally, yes. If you need to record video for hours and hours, you won’t be able to do better than an eight dollar camera and four dollars in parts.

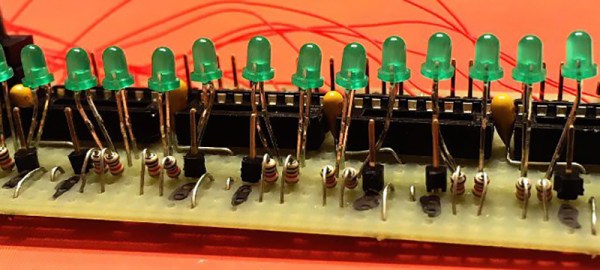

He uses a very clever arrangement of six sensors to get four virtual strings. Each sensor scans a 25-degree field of view. Three adjacent sensors are used to define a string, with the string being in the overlap of the outer two of those sensors. The middle sensor is used for the distance data.

He uses a very clever arrangement of six sensors to get four virtual strings. Each sensor scans a 25-degree field of view. Three adjacent sensors are used to define a string, with the string being in the overlap of the outer two of those sensors. The middle sensor is used for the distance data.