If you find yourself in need of chain link fencing, you’d probably just head down to the hardware store. However, [The Q] has shown us that you can make your own at home with a simple machine.

The build starts with a length of pipe, into which spiral slots are cut with an angle grinder. This pipe is the forming tool which shapes the wire into the familiar chain-link design. The pipe is then welded onto a backing plate, and fitted with a removable handcrank that turns a flat bar. Feed wire into the spiral groove, turn the crank, and out comes wire in the shape required.

From there, formed lengths of wire can be linked up into a fence of any desired size. Of course, fastening each end of the fence is left as an exercise for the reader, and the ends are sharp and unfinished. However, if you don’t like the chain link fencing on sale at your local hardware store, or you want to weave your own in some fancy type of wire, this machine could be just the thing you need.

We’ve seen similar designs before too, but on more of a doll-house scale. Video after the break.

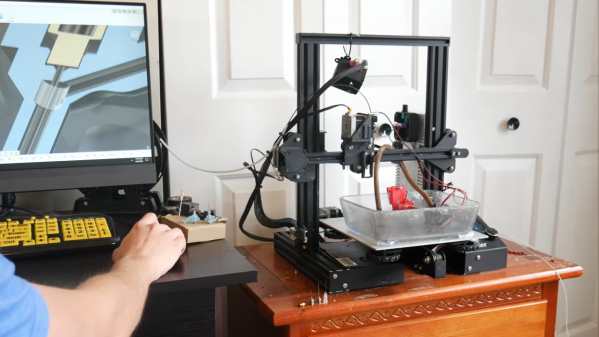

Using a shop vac is fine at smaller scales, but they can quickly be filled up on bigger jobs. To stop it getting filled up as quickly and wasting vacuum bags, [rctestflight] wanted to build a 3D-printed cyclonic separator to catch and dump the heavier-than-air particles from the routing process into an attached bucket.

Using a shop vac is fine at smaller scales, but they can quickly be filled up on bigger jobs. To stop it getting filled up as quickly and wasting vacuum bags, [rctestflight] wanted to build a 3D-printed cyclonic separator to catch and dump the heavier-than-air particles from the routing process into an attached bucket.

There is also a separate

There is also a separate