For electronics aficionados, there are few devices cooler than music synthesizers. The first synths were baroque confabulations of opamps and ladder filters. In the 70s and 80s, synths began their inexorable march toward digitization. There were wavetable synths that stored samples on 27-series EPROMs. Synths on a chip, like the MOS 6581 “SID chip”, are still venerated today. For his Hackaday Prize entry, [Tim] is building his own synthesizer from scratch. It isn’t a copy of an old synth, instead it’s a completely modern synthesizer with a classic sound.

[Tim] is a former game developer and has already released a synthesizer of sorts. Rhythm Core Alpha 2 for the Nintendo DSi and 3DS is a fully functional synthesizer, but the limitations of the Nintendo hardware made [Tim] want to build his own synth from scratch.

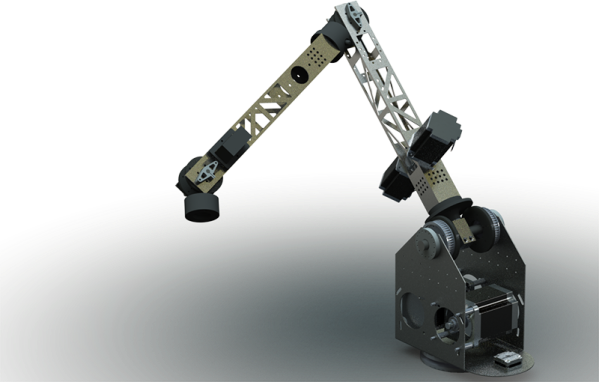

The specs for the synth are more of a wish list, but already [Tim] has a few design features nailed down. This is a virtual analog synth, where everything is digital and handled by DSP algorithms. It’s polyphonic and MIDI capable, with buttons and dials for almost every parameter. For the few things you can’t do with a knob, [Tim] is including a touch screen display.

[Tim] already has the synthesis model working, and from the videos he’s put together, the whole thing sounds pretty good. The next step is turning a bunch of wires, breadboards, and components into something that looks like an instrument. We can’t wait to see how this one turns out!

You can check out a few of [Tim]’s synth videos below.