Ernő Rubik has much to answer for when it comes to the legacy of his namesake cube. It has both enthralled and tormented generations, allowing some to grandstand in the playground while others are forced to admit defeat in the face of a seemingly intractable puzzle. It just so happens that [Tom Parker] has been working on a Rubik’s cube with a novel magnetic design.

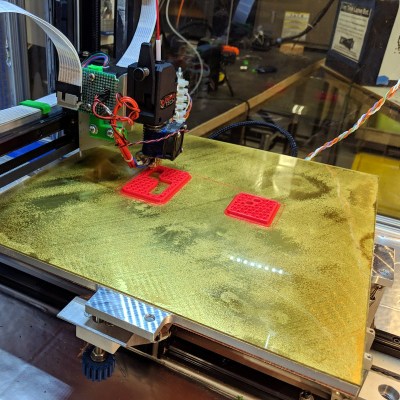

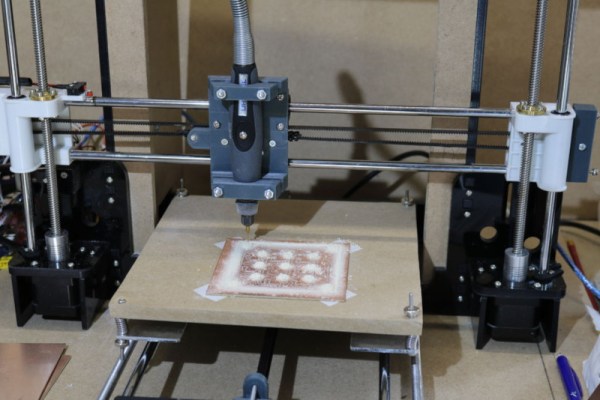

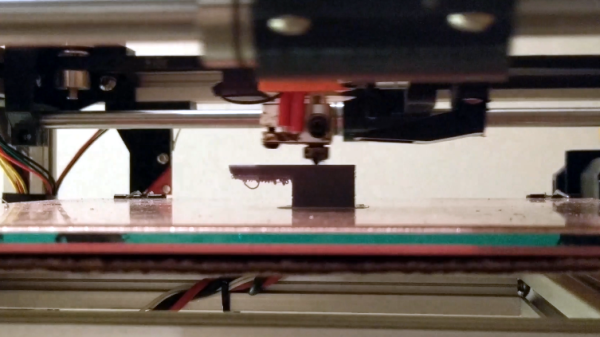

Yes, that’s right – [Tom]’s cube eschews the traditional rotating and sliding mechanism of the original cube, instead replacing it all with magnets. Each segment of the cube, along with the hidden center piece, is 3D printed. Through using a fused deposition printer, and pausing the print at certain layers, it’s possible to embed the magnets inside the part during the printing process.

[Tom] provides several different versions of the parts, to suit printers of different capabilities. The final cube allows both regular Rubik’s cube movements, but also allows for the player to cheat and reassemble it without having to throw it forcefully against the wall first like the original toy.

It’s an interesting build, and a great one to get to grips with the techniques involved in embedding parts in 3D prints. It may not be capable of solving itself, but we’ve seen another build that can pull off that impressive feat. Video after the break.

[critsrandom] shared the method

[critsrandom] shared the method

University of Michigan have figured out a way to

University of Michigan have figured out a way to