We’ve been following the ups and downs of Radio Shack for a while now, and it looks like another chapter is about to be penned in the storied retailer’s biography – and not Chapter 11 bankruptcy this time.

According to the ARRL website and major media reports, up to 50 of the 147 US locations of HobbyTown, the brick-and-mortar retailer of RC and other hobby supplies, will soon host a “RadioShack Express” outlet. Each outlet will be up to 500 square feet of retail space devoted to electronic components that would be of use to HobbyTown’s core customer base, as well as other merchandise and services.

HobbyTown locations in Mooresville, North Carolina, and Ontario, Ohio, will be among the first stores to get the RadioShack Express treatment. Current employees of the franchisees will staff the store-within-a-store, which will be stocked with RadioShack merchandise purchased by the store. Stores with Express outlets will have special RadioShack branding inside and out to attract customers. There’s talk of the deal being extended chain-wide if the pilot program goes well.

Back from the Ashes?

This is obviously great news for the beleaguered electronics retailer that was once a neighborhood fixture. True, its parts selection was often less than complete, more so in recent years than in the chain’s heyday in the mid-1970s and early 1980s. And it’s true that prices were often astronomical compared to buying online. But on a Sunday afternoon, The Shack was a lifesaver for that last minute part needed to finish a project, and the premium was well worth the convenience. Watching the decline of the chain and seeing stores disappear one by one was a slow, sad process, so that makes this seems like an unqualified positive development.

But is it? On the face of it, there’s a lot of synergy between the HobbyTown offerings and what could be stocked in a RadioShack Express. I’ve never actually visited a HobbyTown myself — I plan to fix that now that I know I’ve got an outlet nearby, even if it doesn’t appear to be on the list of 50 early Express locations — so I can only go by what I see listed online for merchandise. But a store that sells every conceivable part for RC cars and planes, drones, model rockets, and STEM-related toys and kits seems a likely place to find customers for RadioShack’s offerings.

It won’t be clear until someone sees one of these Express kiosks first hand and reports back, but it seems like we might see something like the old “cabinet o’ components” that was found in the back of the most recent incarnation of RadioShack retail stores, along with a few shelves full of things like solder, wire, and tools. There may also be some items in the Arduino-Pi space, which would be really exciting, although that might run afoul of existing HobbyTown offerings. Still, one-stop shopping of everything from servos to MOSFETs would be a huge win for electronics hobbyists.

Not the Cell Phones Again!

But there may be cause for concern. Reports are that RadioShack Express locations will also offer services such as cell phone repairs. Dipping a toe into the cell phone market seemed to be the beginning of the end for RadioShack the first time through, and by the time it was clear to everyone that the chain was on death’s door, it was hard to go into a RadioShack store without being bombarded by cell phone sales pitches. To be brutally frank, I don’t take the early inclusion of cell phone repairs as an encouraging sign of the long-term viability of the RadioShack Express concept. Do we really need another place that fixes cell phones? The areas that HobbyTown stores tend to locate are rife with places that fix phones already, so I just don’t see the point. And it just smacks of the bad old days of RadioShack.

Still, I’m cautiously optimistic that this is a positive development for RadioShack, and I think it’s a win for electronics hobbyists overall. I’ll be keeping my eye on my local HobbyTown for the return of that iconic RadioShack logo, and looking forward to the day that I can pay a buck for a resistor again. Until then, if any readers happen to be near one of the combined locations when they open next week, we’d love a boots-on-the-ground report. Post your observations in the comments below, and pix or it didn’t happen.

[via r/amateurradio]

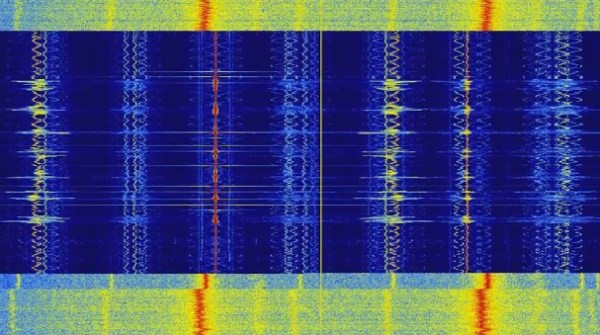

His experiment was simple enough. He picked up a Baofeng handheld radio transceiver to transmit messages containing a call sign and some speech. He then used a 0.5 meter antenna to receive it and a little connecting hardware and a NooElec SDR dongle to get it into his laptop. There he used SDRSharp to process the messages and output a WAV file. He then passed that on to the AI, Google’s Cloud Speech-to-Text service, to convert it to text.

His experiment was simple enough. He picked up a Baofeng handheld radio transceiver to transmit messages containing a call sign and some speech. He then used a 0.5 meter antenna to receive it and a little connecting hardware and a NooElec SDR dongle to get it into his laptop. There he used SDRSharp to process the messages and output a WAV file. He then passed that on to the AI, Google’s Cloud Speech-to-Text service, to convert it to text.