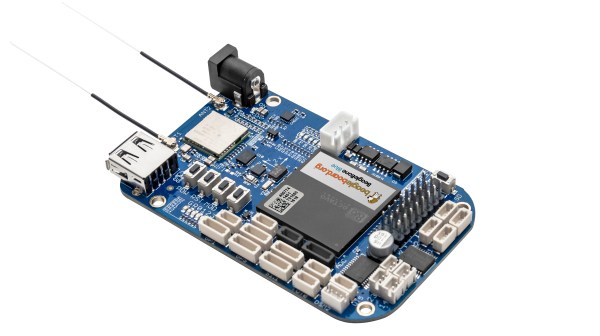

It was announced a day or two ago, but now the PocketBeagle has made its first real-world appearance at the World Maker Faire in New York this weekend. This is a tiny, tiny Linux computer that’s small enough to fit on a keychain, or in an Altoids mini tin. It’s only $25 USD, and from the stock lists on Mouser and Digikey, there are plenty to go around.

The specs for the PocketBeagle are more or less exactly what you would expect from any BeagleBone. There’s an ARM Cortex-A8 running at 1GHz, 512 MB of RAM, and SD card storage. I/O is eight analog inputs, up to 44 digital GPIOs, up to 3 UARTs, 2 I2C busses, 2 SPI busses, and 4 PWM outputs. All of this is packed into the OSD3358 System on a Chip from Octavo Systems.

This isn’t the first time we’ve seen Octavo Systems’ ‘BeagleBone on a Chip’ — Before the release, head Beagle herder [Jason Kridner] built a PocketBone in Eagle, which was shortly followed by [Michael Welling]’s similar efforts in KiCad. The PocketBeagle has been a reality for months, but now it’s accessible to hackers who don’t want to deal with soldering BGA packages.

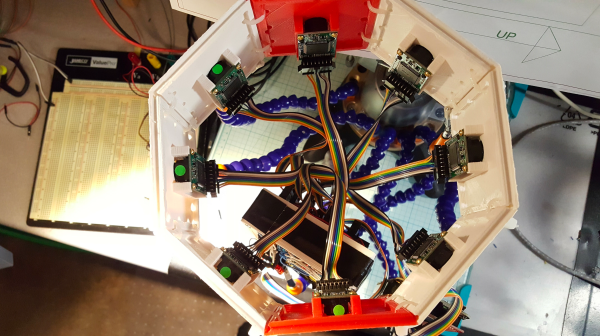

This version of the PocketBeagle is getting close to as Open Source as you can get, with the design files available in Eagle and KiCad. One interesting feature of the PocketBeagle is which pins, busses, and peripherals are enabled by default. The killer feature of the BeagleBone has always been the PRUs — programmable real-time units — that enable vast arrays of LEDs, fast steppers for CNC machines, and DMA tomfoolery. The pins for the PRUs on the PocketBeagle are set up by default, with no need to screw around with configurations, modules, or drivers.