There are many ways to build a radio receiver, but most have a few things in common, such as oscillators, tuned circuits, detectors, mixers, and amplifiers. Put those together in the right order and you’ve got a receiver ready to tune in whatever you want to listen to. But if you don’t really care about tuning and want to hear everything all at once, that greatly simplifies the job and leaves you with something like this homebrew all-band receiver.

Granted, dispensing with everything but a detector and an audio amplifier will seriously limit any receiver’s capabilities. But that wasn’t really a design concern for [Ido Roseman], who was in search of a simple and unobtrusive way to monitor air traffic control conversations while flying. True, there are commercially available radios that tune the aviation bands, and there are plenty of software-defined radio (SDR) options, but air travel authorities and fellow travelers alike may take a dim view of an antenna sticking out of a pocket.

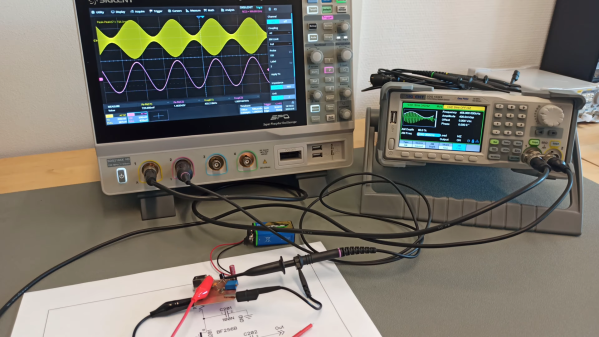

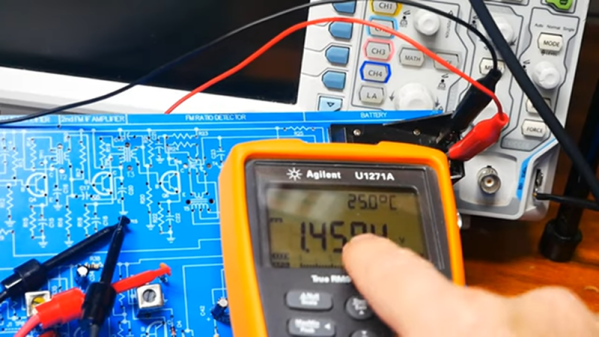

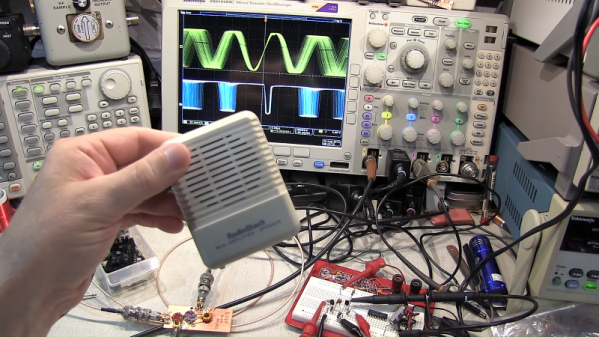

So [Ido] did a little digging and found a dead-simple circuit that can receive signals from the medium-wave bands up into the VHF range without regard for modulation. The basic circuit is a Schottky diode detector between an antenna and a high-gain audio amplifier driving high-impedance headphones; [Ido] built a variation that also has an LM386 amplifier stage to allow the use of regular earbuds, which along with a simple 3D-printed case aids in the receiver’s stealth.

With only a short piece of wire as an antenna, reception is limited to nearby powerful transmitters, but that makes it suitable for getting at least the pilot side of ATC conversations. It works surprisingly well — [Ido] included a few clips that are perfectly understandable, even if the receiver also captured things like cell phones chirping and what sounds like random sferics. It seems like a fun circuit to play with, although with our luck we’d probably not try to take it on a plane.