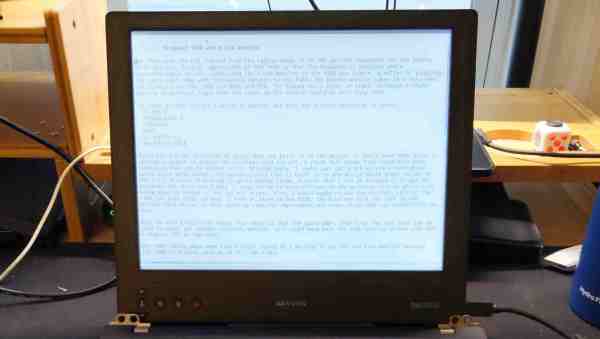

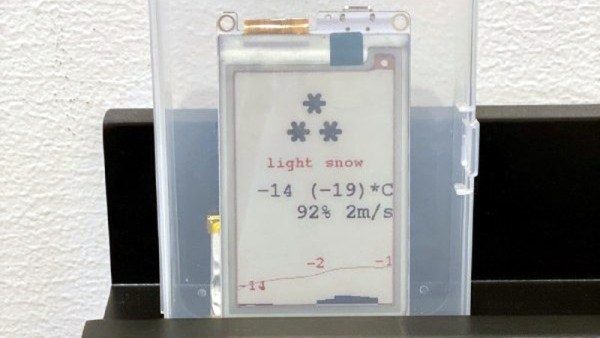

For a monochrome display where refresh rate isn’t particularly important, there’s almost no better option than an E Ink display. They’re available in plenty of sizes and at various price points, but there’s almost no option cheaper than repurposing something mass-produced and widely available like an E Ink (sometime also called eInk or ePaper) price tag. At least, once all of the reverse engineering is complete.

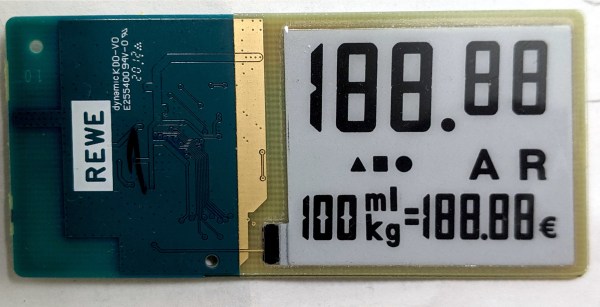

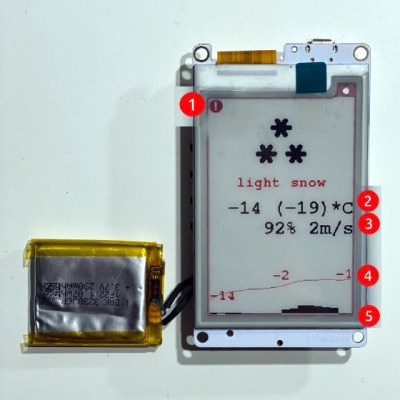

[Dmitry Grinberg] has been making his way through a ton of different E Ink modules, unlocking their secrets as he goes. In this case he set about reverse engineering the unknown microcontroller on the small, cheap display show here. Initial research showed an obscure chip from the ZBS24x family, packaged with a SSD1623L2 E Ink controller. From there, he was able to solder to the communications wires and start talking to the device over ISP.

This endeavor is an impressive deep dive into the world of microcontrollers, from probing various registers to unlocking features one by one. It’s running an 8051 core so [Dmitry] gives a bit of background to help us all follow along, though it’s still a pretty impressive slog to fully take control of the system.

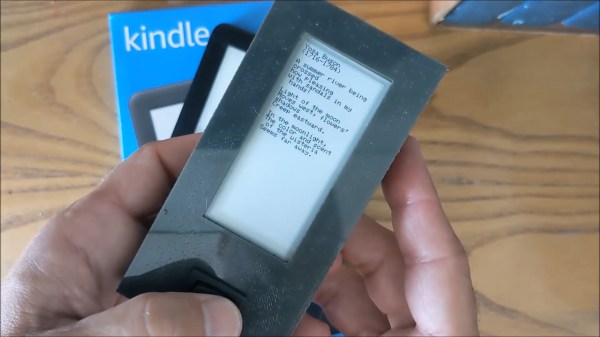

If you happen to have one of these price tags on hand it’s an invaluable resource to have to reprogram it, but it’s a great read in general as well. On the other hand, if you’re more interested in reverse-engineering various displays, take a look at this art installation which spans 50 years of working display technologies.