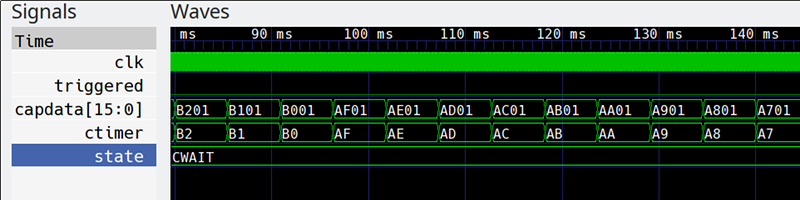

You finally finish writing the Verilog for that amazing new DSP function that will revolutionize human society and make you rich. Does it work? Your first instinct, of course, is to blow it into your FPGA of choice and see if it works. If it does, that was a great idea. If it doesn’t, it was a terrible idea because — typically — it is hard to look inside the FPGA. That’s why you’ll typical simulate your logic on a desktop computer before you commit it to the FPGA. But that means you have to delay gratification long enough to write a testbench — a piece of hardware description language (HDL) code that exercises the function you wrote. In this post I’ll show you a small piece of software that can read your Verilog module and automatically create most of a testbench for you. The code originally came from GitHub, but I wanted to make some changes to it, so I forked it and I’ll tell you about the changes I made. This isn’t specific to a particular FPGA. Any Verilog project can use the tool to generate a simple starter testbench.

Writing a testbench isn’t that hard. You usually use the same language you wrote the original code in but since it won’t reside in silicon, you can do things in the simulator that you can’t get away with in code that you’ll synthesize. However, it is a bit painful to have to always write more or less the same code, especially if you have a lot of modules you want to test. But it is a good idea to test small modules before linking them together and then test them linked together, too. With this little Python script, it is very easy to generate a simple testbench and then further elaborate it. It isn’t life-changing, but it does save some time. If you want to try this out, you’ll need something to run the Python script on, of course. You also need a Verilog simulator or you can use EDA Playground to try all this out in your browser.