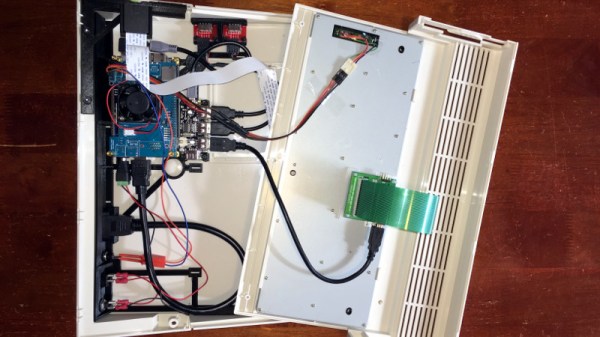

Got $4,000 to spend? Even if you don’t, keep reading — especially if you develop with FPGAs. Exostiv’s FPGA debugging setup costs around $4K although if you are in need of debugging a complex FPGA design and your time has any value, that might not be very expensive. Then again, most of us have a lot of trouble justifying a $4,000 piece of test gear. But we wanted to think about what Exostiv is doing and why we don’t see more of it. Traditionally, debugging FPGAs meant using JTAG and possibly some custom blocks that act like a logic analyzer and chew up real estate on your device. Exostiv also uses some of your device, but instead of building a JTAG-communicating logic analyzer it… well, here’s what their website says:

EXOSTIV IP uses the MGTs (Multi-Gigabit Transceivers) to flow captured data out of the FPGA to an external memory. EXOSTIV IP supports repeating captures of up to 32,768 internal nodes simultaneously at the FPGA’s speed of operation (16 data sets x 2,048 bits).

EXOSTIV IP provides dynamic multiplexer controls to capture even more data sets without the need to recompile. Dynamic ON/OFF controls of data sets let you select the data set and preserve the MGT’s bandwidth for when deeper captures of a reduced set of data is required.

In a nutshell, this means they use high-speed communications to send raw data to a box that has memory and connects back to a PC. That means they can store more data, have more data come out of the chip over a certain time frame, and do sophisticated processing. You can see a video about the device below, and there are more detailed videos on their channel, as well.

Continue reading “Exostiv FPGA Debugging Might Be A Bargain” →