I use open source software almost exclusively; at least on the desktop — the phone is another matter, sadly. And I do a lot of stuff with and on computers. Folks outside of the free software scene are still a little surprised when small programs are free to use and modify, but they’re downright skeptical when it comes to the big works of professional software. It’s one thing to write xeyes, but how about something to rival Photoshop, or Altium?

Of course, we all know the answer — mostly. None of the “big” software packages work exactly the same as their closed-source counterparts, often missing a few features here and gaining a few there, or following a different workflow. That’s OK, different closed-source programs work differently as well. I’m not here to argue that GIMP is better than Photoshop, but rather to point out what I really love about open software: it caters to the little guys and gals, the niche users, and the specialists. Or rather, it lets them cater to themselves.

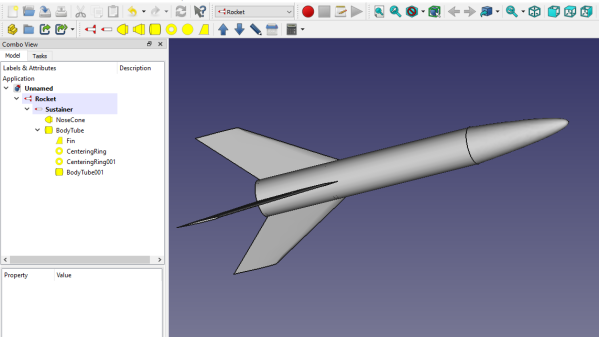

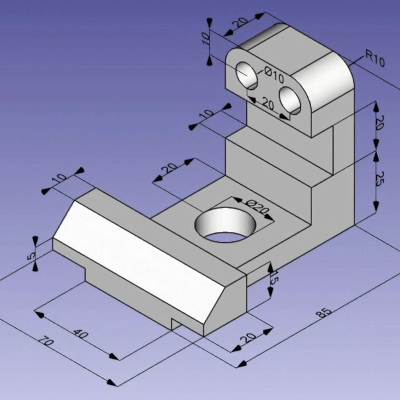

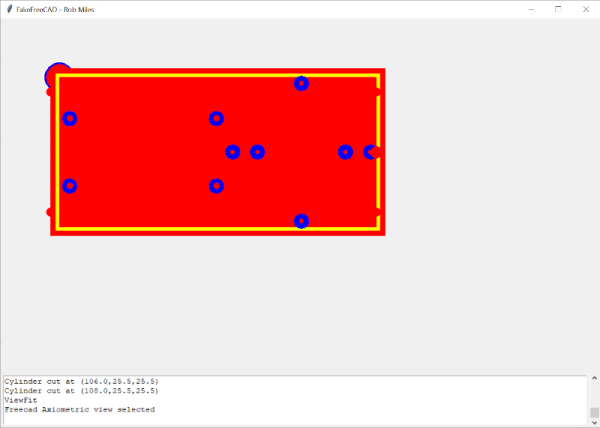

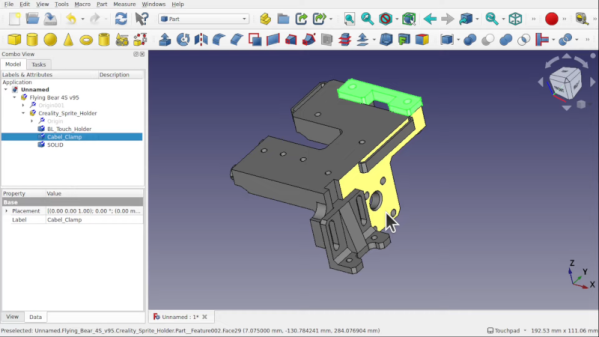

I just started learning FreeCAD for a CNC milling project, and it’s awesome. I’ve used Fusion 360, and although FreeCAD isn’t “the same” as Fusion 360, it has most of the features that I need. But it’s the quirky features that set it apart.

I just started learning FreeCAD for a CNC milling project, and it’s awesome. I’ve used Fusion 360, and although FreeCAD isn’t “the same” as Fusion 360, it has most of the features that I need. But it’s the quirky features that set it apart.

The central workflow is to pick a “workbench” where specific tasks are carried out, and then you take your part to each bench, operate on it, and then move to the next one you need. But the critical bit here is that a good number of the workbenches are contributed to the open project by people who have had particular niche needs. For me, for instance, I’ve done most of my 3D modelling for 3D printing using OpenSCAD, which is kinda niche, but also the language that underpins Thingiverse’s customizer functionality. Does Fusion 360 seamlessly import my OpenSCAD work? Nope. Does FreeCAD? Yup, because some other nerd was in my shoes.

And then I started thinking of the other big free projects. Inkscape has plugins that let you create Gcode to drive CNC mills or strange plotters. Why? Because nerds love eggbots. GIMP has plugins for every imaginable image transformation — things that 99% of graphic artists will never use, and so Adobe has no incentive to incorporate.

Open source lets you scratch your own itch, and share your solution with others. The features of for-pay, closed-source software are driven by the masses: “is this a feature that enough of our customers want?” The features of open-source software are driven by the freaky ideas of nerds just like me. Vive la différence!

making uploading firmware a breeze. To that end, a USB port is also provided, hooked up to the uC with the cheap CP2102 USB bridge chip as per most Arduino-like designs. The thing that makes this build a little unusual is the ethernet port. The hardware side of things is taken care of with the

making uploading firmware a breeze. To that end, a USB port is also provided, hooked up to the uC with the cheap CP2102 USB bridge chip as per most Arduino-like designs. The thing that makes this build a little unusual is the ethernet port. The hardware side of things is taken care of with the

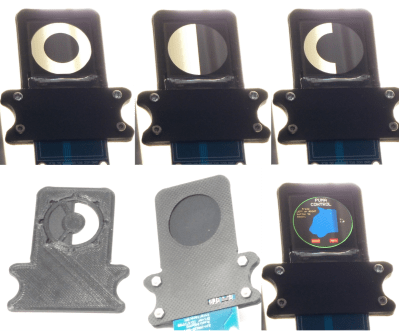

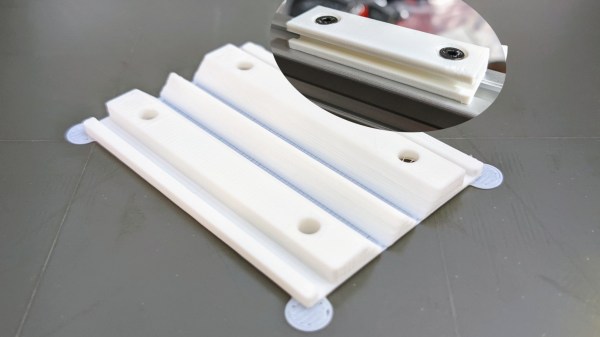

The example Chris provides is a Eurorack rail segment — due to the kind of overhangs required, you’d be inclined to print it vertically, taking a hit to the print time and introducing structural weaknesses. With this trick, you absolutely don’t have to! You can also go way further and 3D print a single-piece foldable

The example Chris provides is a Eurorack rail segment — due to the kind of overhangs required, you’d be inclined to print it vertically, taking a hit to the print time and introducing structural weaknesses. With this trick, you absolutely don’t have to! You can also go way further and 3D print a single-piece foldable