Before you attempt to solve a problem, you must first study the problem. If there’s a problem with the environment, you must therefore study the environment at a scale never seen before. For this year’s Hackaday Prize, there are a lot of projects that aim to do just that. Here are a few of them:

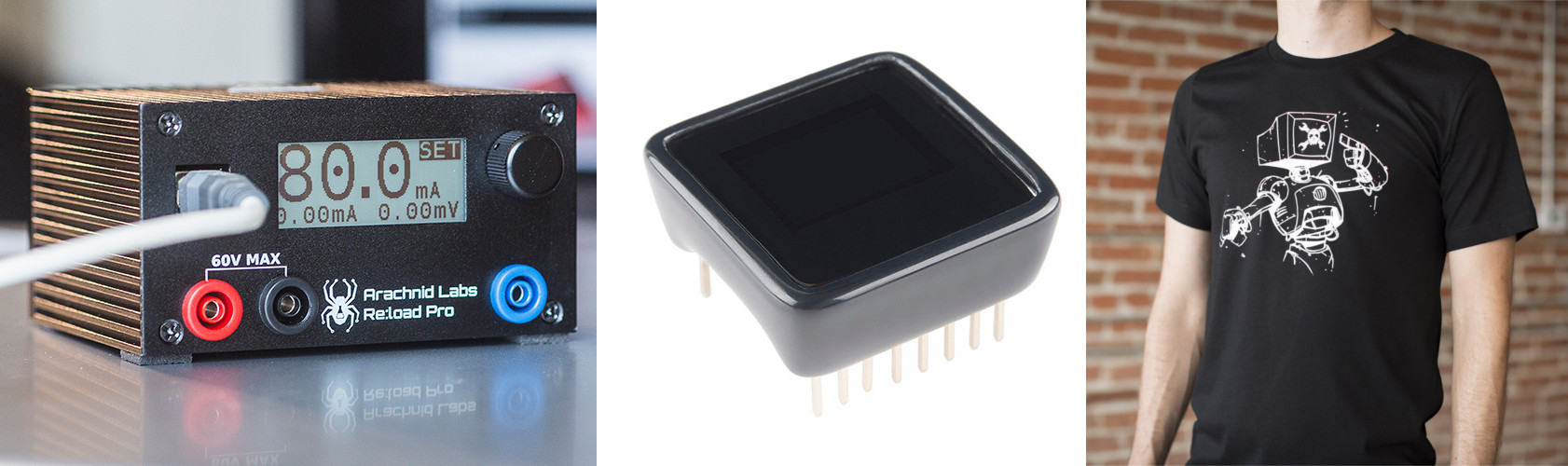

[Pure Engineering]’s C12666 Micro Spectrometer has applications ranging from detecting if fruit is ripe, telling you to put sunscreen on, to detecting oil spills. Like the title says, it’s based on the Hamamatsu C12666MA spectrometer, a very tiny MEMS spectrometer that can sort light by wavelength from 340 to 780nm.

The project is to build a proper breakout board for this spectrometer. The best technologies are enabling technologies, and we can’t wait to see all the cool stuff that’s made with this sensor.

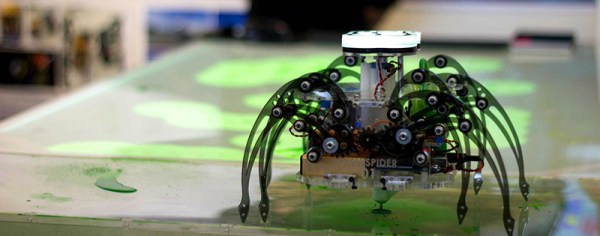

[radu.motisan]’s portable environmental monitor isn’t just one sensor, but an entire suite of them. The design of the project includes toxic and flammable gas sensors, radiation detectors, dust sensors, and radiation detectors packaged together in a neat, convenient package.

[radu] has already seen some success with environmental sensors and The Hackaday Prize; last year, his entry, the uRADMonitor placed in the top fifty for creating a global network of radiation sensors.

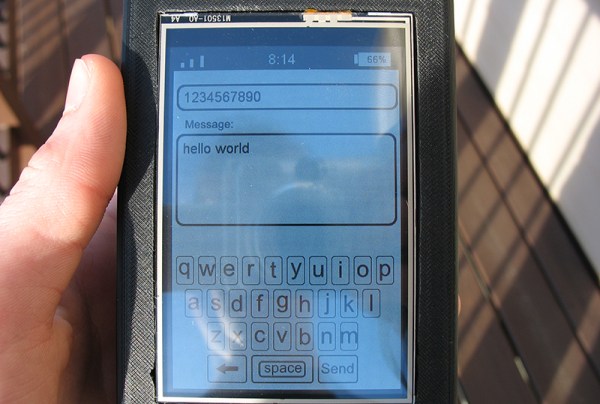

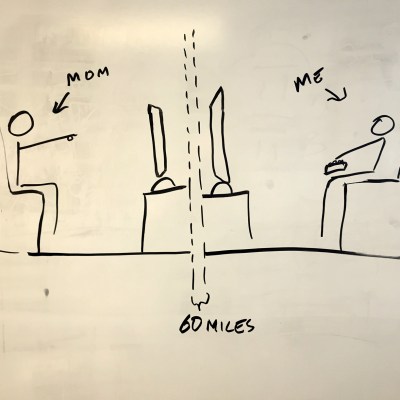

Watching out for each other is complicated by distance. We saw a few entries that try to alleviate that, like the

Watching out for each other is complicated by distance. We saw a few entries that try to alleviate that, like the  Continuing on the note of simplified communications is

Continuing on the note of simplified communications is