In the early days of AI, a common example program was the hexapawn game. This extremely simplified version of a chess program learned to play with your help. When the computer made a bad move, you’d punish it. However, people quickly realized they could punish good moves to ensure they always won against the computer. Large language models (LLMs) seem to know “everything,” but everything is whatever happens to be on the Internet, seahorse emojis and all. That got [Hayk Grigorian] thinking, so he built TimeCapsule LLM to have AI with only historical data.

Sure, you could tell a modern chatbot to pretend it was in, say, 1875 London and answer accordingly. However, you have to remember that chatbots are statistical in nature, so they could easily slip in modern knowledge. Since TimeCapsule only knows data from 1875 and earlier, it will be happy to tell you that travel to the moon is impossible, for example. If you ask a traditional LLM to roleplay, it will often hint at things you know to be true, but would not have been known by anyone of that particular time period.

Chatting with ChatGPT and telling it that it was a person living in Glasgow in 1200 limited its knowledge somewhat. Yet it was also able to hint about North America and the existence of the atom. Granted, the Norse apparently found North America around the year 1000, and Democritus wrote about indivisible matter in the fifth century. But that knowledge would not have been widespread among common people in the year 1200. Training on period texts would surely give a better representation of a historical person.

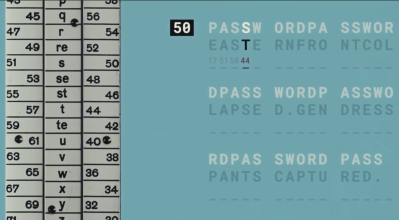

The model uses texts from 1800 to 1875 published in London. In total, there is about 90 GB of text files in the training corpus. Is this practical? There is academic interest in recreating period-accurate models to study history. Some also see it as a way to track both biases of the period and contrast them with biases found in data today. Of course, unlike the Internet, surviving documents from the 1800s are less likely to have trivialities in them, so it isn’t clear just how accurate a model like this would be for that sort of purpose.

Instead of reading the news, LLMs can write it. Just remember that the statistical nature of LLMs makes them easy to manipulate during training, too.

Featured Art: Royal Courts of Justice in London about 1870, Public Domain

![[Mark] shows off footage from a D1 master on the repaired deck](https://hackaday.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/Reboot_saved_feat.png?w=600&h=450)