Although most of us simultaneously accept the premise that magnets are quite literally everywhere and that few people know how they work, a major problem with magnets today is that they tend to rely on so-called rare-earth elements.

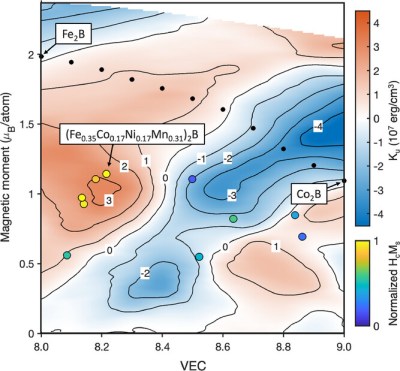

Although firmly in the top 5 of misnomers, these abundant elements are hard to mine and isolate, which means that finding alternatives to their use is much desired. Fortunately the field of high entropy alloys (HEAs) offers hope here, with [Beeson] and colleagues recently demonstrating a rare-earth-free material that could be used for magnets.

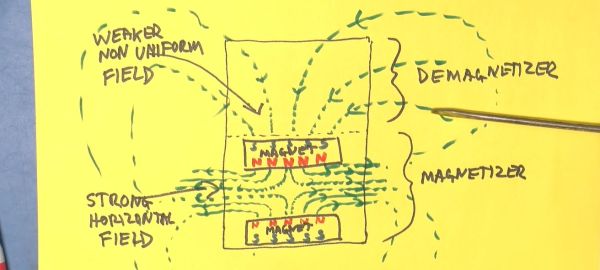

Although many materials can be magnetic, to make a good magnet you need the material in question to be both magnetically anisotropic and posses a clear easy axis. This basically means a material that has strong preferential magnetic directions, with the easy axis being the orientation which is the most energetically favorable.

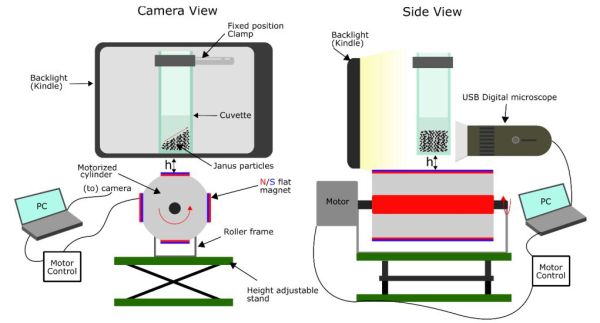

Through experimental validation with magnetic coercion it was determined that of the tested boride films, the (FeCoNiMn)2B variant with a specific deposition order showed the strongest anisotropy. What is interesting in this study is how much the way that the elements are added and in which way determines the final properties of the boride, which is one of the reasons why HEAs are such a hot topic of research currently.

Of course, this is just an early proof-of-concept, but it shows the promise of HEAs when it comes to replacing other types of anisotropic materials, in particular where – as noted in the paper – normally rare-earths are added to gain the properties that these researchers achieved without these elements being required.