Every person who reads these pages is likely to have encountered a neodymium magnet. Most of us interact with them on a daily basis, so it is easy to assume that the process for their manufacture must be simple since they are everywhere. That is not the case, and there is value in knowing how the magnets are manufactured so that the next time you pick one up or put a reminder on the fridge you can appreciate the labor that goes into one.

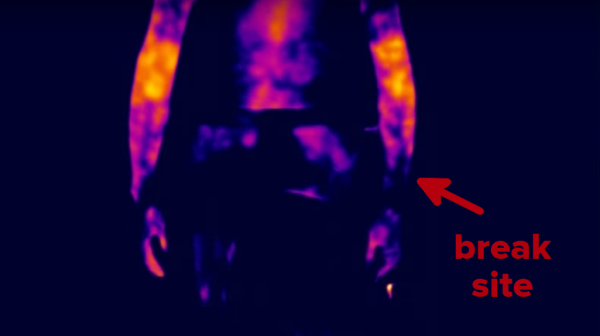

[Michael Brand] writes the Super Magnet Man blog and he walks us through the high-level steps of neodymium magnet production. It would be a flat-out lie to say it was easy, but you’ll learn what goes into them and why you don’t want to lick a broken hard-drive magnet and why it will turn to powder in your mouth. Neodymium magnets are probably unlikely to be produced at this level in a garage lab, but we would love to be proved wrong.

We see these magnets everywhere, from homemade encoder disks, cartesian coordinate tables, to a super low-power motor.