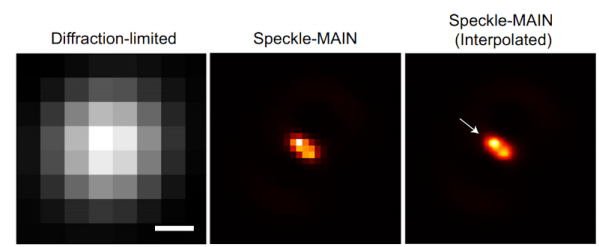

Optical microscopes depend on light, of course, but they are also limited by that same light. Typically, anything under 200 nanometers just blurs together because of the wavelength of the light being used to observe it. However, engineers at the University of California San Diego have published their results using a hyperbolic metamaterial composed of silver and silica to drive optical microscopy down to below 40 nanometers. You can find the original paper online, also.

The technique also requires image processing. Light passing through the metamaterial breaks into speckles that produce low-resolution images that can combine to form high-resolution images. This so-called structured illumination technique isn’t exactly new, but previous techniques allowed about 100-nanometer resolution, much less than what the researchers were able to find using this material.

Continue reading “Optical Microscope Resolves Down To 40 Nanometers”

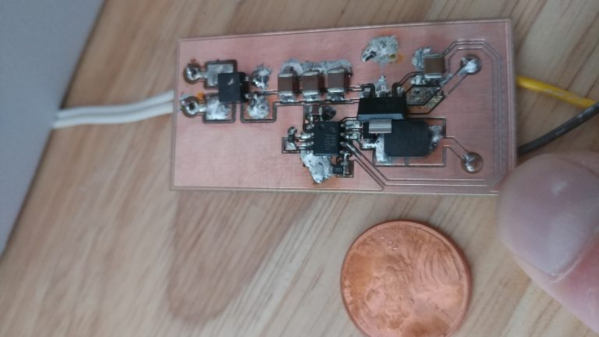

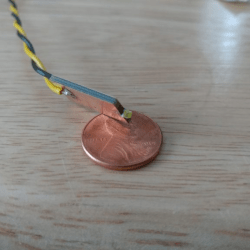

Usually, such builds are plain vanilla and not much to write in about, but [smellsofbikes] has a few tricks worth taking note of. He found a couple of high power, SMD LEDs in his parts bin. They were just slightly wider than 1.6 mm across the terminals. So he took a piece of double sided, copper clad FR4, and edge mounted the LED against one side of the PCB piece, twisting it slightly so he could solder both terminals. This works as a great heat sink for the LED while still having a very narrow profile. This was important as the replacement LED board had to fit the cylinder in which the original lamp was fitted.

Usually, such builds are plain vanilla and not much to write in about, but [smellsofbikes] has a few tricks worth taking note of. He found a couple of high power, SMD LEDs in his parts bin. They were just slightly wider than 1.6 mm across the terminals. So he took a piece of double sided, copper clad FR4, and edge mounted the LED against one side of the PCB piece, twisting it slightly so he could solder both terminals. This works as a great heat sink for the LED while still having a very narrow profile. This was important as the replacement LED board had to fit the cylinder in which the original lamp was fitted.