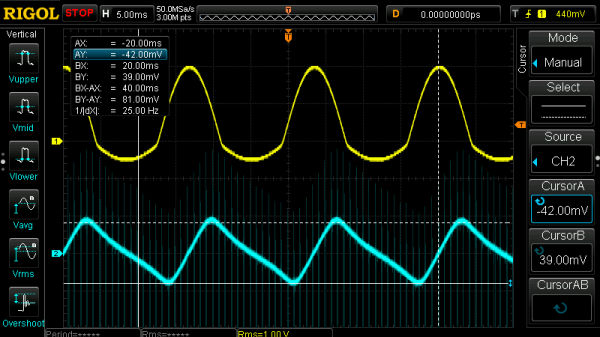

The Rigol DS1054Zed is the oscilloscope you want. If you don’t have an oscilloscope, this is the scope that has the power and features you need, it’s cheap, and the people who do hardware hacks already have one. That means there’s a wealth of hardware hacks for this oscilloscope. One small problem with the ‘Zed is the fact that capturing an image from the screen is overly complicated, and the official documentation requires dedicated software and a lot of rigolmarole. Now there’s a simple python script that grabs a screen cap from a Rigol scope.

The usage of this python script is as simple as plugging the DS1054Z into your USB port and running the script. A PNG of whatever is on the screen then appears on your drive. Testing has been done on OS X, and it probably works on Linux and Windows. It’s a simple tool that does one job, glory and hallelujah, people are still designing tools this way.

This work was inspired by the efforts of [cibomahto], who spent some time controlling the Rigol with Linux and Python. This work will plot whatever is being captured by the scope in a window, in Linux, but sometimes you just need a screencap of whatever is on the scope; that’s why there were weird Polaroid adapters for HP scopes in the day.

Yes, it’s a simple tool that does one job, but if you need that tool, you really need that tool. [rdpoor] is looking for a few people to test it out, and of course pull requests are accepted.