We’ve all been there. Your roommate is finally out of the house and you have some time alone. Wait a minute… your roommate never said when they would be back. It would be nice to be warned ahead of time. What should you do? [Mattia] racked his brain for a solution to this problem when he realized it was so simple. His roommates have been warning him all along. He just wasn’t listening.

Most Hackaday readers probably have a WiFi network in their homes. Most people nowadays have mobile phones that are configured to automatically connect to these networks when they are in range. This is usually smart because it can save you money by not using your expensive 4G data plan. [Mattia] realized that he can just watch the wireless network to see when his roommates’ phones suddenly appear. If their devices appear on the network, it’s likely that they have just arrived and are on their way to the front door.

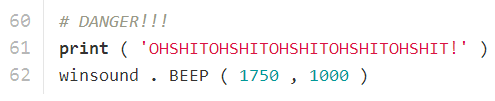

Enter wifinder. Wifinder is a simple Python script that Mattia wrote to constantly scan the network and alert him to new devices. Once his roommates are gone, Mattia can start the script. It will then run NMap to get a list of all devices on the network. It periodically runs NMap after this, comparing the new host list to the old one. If any new devices show up, it alerts with an audible beep and a rather hilarious output string. This type of scanning is nothing new to those in the network security field, but the use case is rather novel.