No matter what you do or say on the Internet, you’re always doing it wrong. Keyboard commandos are ready to pounce and tell you how it’s “ackchyually” supposed to be done. And so it was of little surprise when [Jason] of Fireball Tools was taken to task by the armchair millwright for his supposedly deficient method of filing metal.

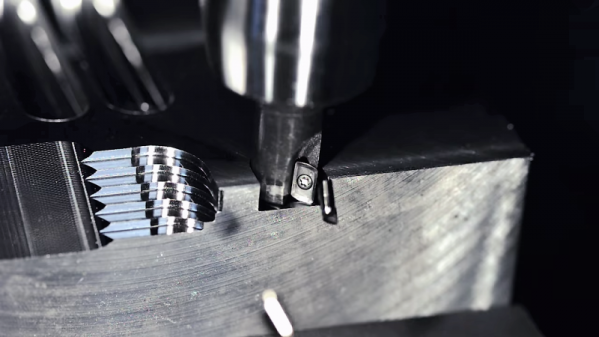

But [Jason] chose to fight back not with words but deeds, building a system to test alternative methods of filing. His filing style is to leave the file in contact with the stock on both the front- and back-strokes, which enraged those who claim that a file must never be dragged back over the workpiece, lest the teeth become dull. The first video below shows the build of the test rig, which leveraged his enormous Cinncinatti shaper as the prime mover, as well as a pneumatic jig to hold the workpiece and imitate both styles of filing. Part two below shows the test rig in action, and [Jason] really outdoes himself with his experimental approach. He tested three different grades of Pferd files — nothing but the best, no expense spared — and did duplicates of each run using both the Internet-approved style and his lazier style.

The result? We won’t spoil that for you, but suffice it to say that the hive mind isn’t always right. And what’s more, [Jason]’s careful myth-busting yielded a few interesting and unexpected results. His channel is full of great shop tips and interesting builds, so check him out if you want to see how metalworking is done.

Continue reading “Science Vs Internet Trolls: Testing Another Kind Of File System”