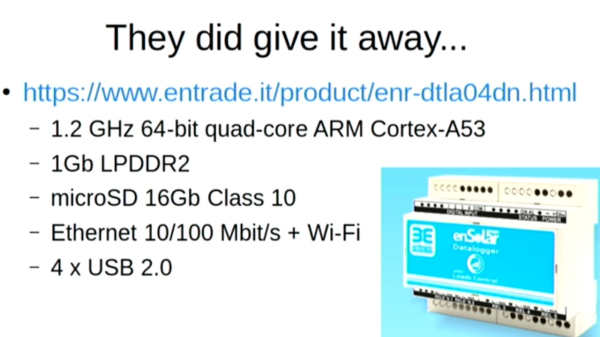

There’s quite a few devices on the market that contain a Raspberry Pi as their core, and after becoming a proud owner of a solar roof, [Paolo Bonzini] has found himself with an Entrade ENR-DTLA04DN datalogger which – let’s just say, it had some of the signs, and at FOSDEM 2023, he told us all about it. Installed under the promise of local-only logging, the datalogger gave away its nature with a Raspberry Pi logo-emblazoned power brick, a spec sheet identical to that of a Pi 3, and a MAC address belonging to the Raspberry Pi Foundation. That spec sheet also mentioned a MicroSD card – which eventually died, prompting [Paolo] to take the cover off. He dumped the faulty SD card, then replaced it – and put his own SSH keys on the device while at it.

At this point, Entrade no longer offered devices with local logging, only the option of cloud logging – free, but only for five years, clearly not an option if you like your home cloud-free; the local logging was not flawless either, and thus, the device was worth exploring. A quick peek at the filesystem netted him two large statically-compiled binaries, and strace gave him a way to snoop on RS485 communications between the datalogger and the solar roof-paired inverter. Next, he dug into the binaries, collecting information on how this device did its work. Previously, he found that the device provided an undocumented API over HTTP while connected to his network, and comparing the API’s workings to the data inside the binary netted him some good results – but not enough.

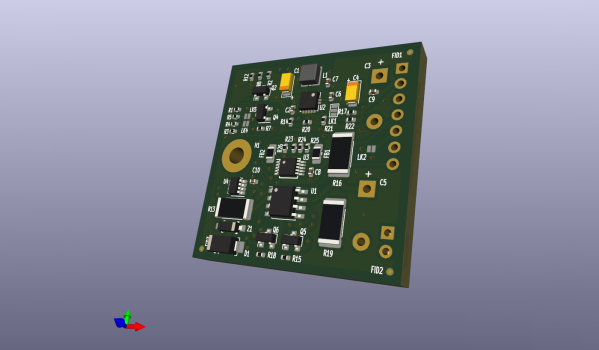

The main binary was identified to be Go code, and [Paolo] shows us a walkthrough on how to reverse-engineer such binaries in radare2, with a small collection of tricks to boot – for instance, grepping the output of strings for GitHub URLs in order to find out the libraries being used. In the end, having reverse-engineered the protocol, he fully rewrote the software, without the annoying bugs of the previous one, and integrated it into his home MQTT network powered by HomeAssistant. As a bonus, he also shows us the datalogger’s main PCB, which turned out to be a peculiar creation – not to spoil the surprise!

We imagine this research isn’t just useful for when you face a similar datalogger’s death, but is also quite handy for those who find themselves at the mercy of the pseudo-free cloud logging plan and would like to opt out. Solar tech seems to be an area where Raspberry Pi boards and proprietary interfaces aren’t uncommon, which is why we see hackers reverse-engineer solar power-related devices – for instance, check out this exploration of a solar inverter’s proprietary protocol to get data out of it, or reverse-engineering an end-of-life decommissioned but perfectly healthy solar inverter’s software to get the service menu password.